Narrative distance part 1: I LET YOU GO

Point of view, verb tense, and a Clare Mackintosh case study

I’m feeling like an alternate name for these mentor columns could be Case Studies, because that’s what I seem to end up doing every month, and I don’t hate it. Now that we’ve covered some basics of story structure and character development, I think it makes sense to consider how much distance you want to put between the reader and those characters in order to best tell the story. I have a whole mess of things to say about narrative distance, some of which I’m saving for next time. This time, I’m going to focus on point of view (first, second, and third) and verb tense.

When I think about how a suspense story should be told, there are four important questions that spring to mind: what information do I want my readers to have access to; is there anything I need to hold back from my readers or otherwise control; how intimate a reading experience do I want my reader to have; and how do I enjoy writing?

What information do I want my readers to have access to?

This question seems simple but can be deceptively tricky to answer, in my personal experience. Or maybe what’s hard is weighing it against the other questions, which might counsel against the perspective that makes it easiest to share information. You can tell the reader just about anything you want with an omniscient perspective, or lots and lots of individual points of view, but it may be harder to impart as intimate a reading experience.

As I mentioned in my last column, I decided to set aside a novel in April. I wrote an early draft in first person. As much as I liked that narration, it was hard to give the reader all the details I wanted for dramatic effect. (Especially because the character was a layperson, not law enforcement, an attorney, or some other professional who’d have tons of access to procedural information.) Contrast that with my first novel, where I used four points of view, one law enforcement and one a former attorney who could explain procedural aspects of the situation to the reader and other characters. Another character was the victim of the crime being investigated. The fourth was contemplating a crime. Between the four of them, I could tell the reader everything I wanted.

Is there anything I need to hold back from my readers or otherwise control?

Whether you’re writing a mystery and need to obscure whodunnit or a thriller with an identity-twist in the middle, you might have something you want to hold back from your readers. Please, do this without cheating. Nothing grinds my gears like reading a first-person narrative that straight up lies to me, in the character’s own head, for no reason besides to drop a nutso twist in the last act. Mislead me, cleverly, and make it make sense!1

How intimate a reading experience do I want my reader to have?

Thus far in my short career, I’ve wanted to impart intimate reading experiences, where readers are in close with the characters, and their emotions and motivations. But there are times when a distant, less intimate voice is super effective. (Think: the cold, matter-of-fact narration in Shirley Jackson’s famous short story, The Lottery.)

I know some writers find first person to be more intimate and third person to be less. Personally, I don’t think intimacy is controlled by the choice between first- and third-person point of view. I’ve read books written in third person where I felt super close to a character, emotionally, and books written in first person where I found the first-person character herself flat and unreachable. (I’ll talk more about other factors that influence narrative distance next time.)

How do I enjoy writing?

This is never not going to matter. If you’ve experimented with lots of styles and think one is “better” but another makes your heart sing and your ink flow, write the one you enjoy! You’re clever. You’ll figure out how to make it work.

You probably already know your options, but let’s run through this English 101 vocab list anyway.

First person: Narrator is a character who relays the story in “I” statements. Example: Gone Girl by Gillian Flynn.

Second person: I have always thought of second person narration as being simply one in which the narrator refers to a “you,” whether the audience for the narrator is another character or the reader herself, beyond the pages. The example I always think of is You by Caroline Kepnes. (Or the epistolary novel Don’t Cry for Me by Daniel Black, which is not suspense but is excellent.) Some sources agree with me. Others say that true second person is only when “you” reaches beyond the story to refer to the reader, like in a choose-your-own-adventure story. I wonder if the purists used to be right but usage has changed and now “second person” is a little broader. That’s what I’m going with, but I am frequently wrong about stuff.

Third-person omniscient: The narrator is all-knowing or god-like, able to convey what each character is thinking or feeling. Example: IDK. Mostly I think of old classics. Maybe I just don’t read enough, but I can’t think of any suspense novels written from an omniscient point of view. One possible example is Stephen King’s ‘Salem’s Lot. Many of the chapters are tied in perspective to a particular character, but several are written from the point of view of the town itself, moving through Jerusalem’s Lot from one townsperson to another, with access to everyone. If you’ve read this book, what do you think? Does that count as omniscient?

Third person limited: The narrator focuses on one character at a time, without knowing or divulging anything unknown to that character herself. Over the course of the book the narration may follow multiple characters (e.g. Mystic River by Dennis Lehane), or the whole story might be tied to one character’s perspective, as in many detective novels (e.g. Tessa Wegert’s Shana Merchant novels).2

Verb tense: Believe it or not, “verb tense” means what tense the verbs are in. Another way to think of it is: is the story being relayed to the reader after it happened or as it happens? (Or even before? Is there such a thing as an entire book written in future tense? Probably. Writers are wild. Drop it in the comments if you know of one!)

The general rule is that consistency is key. But, as with all writing rules, it’s more of a strong suggestion; you should know why the rule exists in order to do well breaking it. The reason, I think, is readability. The more you change the rules of your story’s internal world, the harder your reader has to work to understand the story. (I think this is especially true for verb tenses: switching from past tense to present and back to past reads like an editing error.)

For a single scene, pick a verb tense and point-of-view and stick to it. Deviate only when it’s still grammatically correct, not confusing/hard to read, and effective for storytelling.

As for different scenes and points of view, you may find that you want everyone to use the same rules. Such as: all chapters are written in first person present. This might make for the most readable experience; less work for the reader’s brain. That said, I don’t find it too difficult to switch from quite different perspectives if they’re done consistently. (E.g. character A is always third person past; character B is always first person present.) If you’re a gold-star author (thank you for this concept, Megan Collins), you could even consider using first, second, and third person points of view! (But don’t actually do this unless you’ve got a good reason. You risk being hard to follow, annoying, or downright unreadable.)

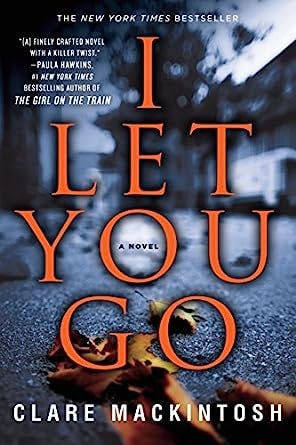

Warnings aside, I’ve seen it done once, and the effect was delightful. Yep, we’ve reached the case study: Clare Mackintosh’s 2011 novel I Let You Go. I’m going to spoil the big midpoint twist and maybe one chapter after it, so, if you decide not to read on, feel free to comment or like before you go!

Now, on to my gold-star example of how to use point of view in suspense.

I didn’t realize this book was Mackintosh’s debut until I started writing this piece. Genius alert! I wonder if she was so bold because she hadn’t heard the standard be-consistent advice. Or maybe she knew she was doing something special. Either way, this book rocked me. Her use of story structure was perfect. She even used an epilogue to punch a hole in the otherwise happy ending, which is one of the better reasons to use an epilogue in a suspense novel.3 But I digress. Let’s focus solely on how she used first-, third-, and second-person point of view. This is your last warning that thar be spoilers ahead.

In a prologue, a woman speaks in first person present tense. She is walking with her young son. She lets go of his hand and he darts out into the street and is hit by a car. The car leaves. Mackintosh’s use of first person and present tense makes the scene visceral and immediate; it puts the reader in the character’s shoes as it happens.

In the first chapter, limited third-person narration introduces the reader to Detective Inspector Ray Stevens, who is investigating the hit and run. His chapters are limited to his point of view and are told in the past tense. These choices remove the detective from the immediacy of the crime and fit the procedural air of his role. Example: “The child’s mother was sitting on a small sofa, her eyes fixed on the blue drawstring school bag clutched on her lap.”

In the second chapter, present-tense, first-person narration introduces a woman who is speaking to a police officer. “He towers over me and I know I should look up, but I can’t bear to. How can he offer me food and drink as though nothing has happened?” This woman, who is eventually named Jenna, replays the accident in her head, blames herself, and eventually flees for the countryside, where she tells no one about the child, the accident, or her old life. Mackintosh’s choices make her scenes feel raw, immediate, and personal.

At the half-mark, the reader realizes that Jenna is not the same person from the prologue. The prologue was the boy’s mother, and Jenna was in the car that hit him. (As Shana Wilson learned at the Hampton’s Whodunnit conference, in a panel including Clare Mackintosh herself, a twist is the answer to the question you didn’t think to ask.) The execution is excellent. As Jenna has been remaking her life and trying to forget the boy who died, who consumes her thoughts, the detectives are aware that the boy’s mother has left town after a long stretch of stalled investigation. While a colleague is trying to locate the missing mother, DI Stevens is tracking down the car, which leads him to Jenna. When she answers the door and it’s Stevens, not his colleague, on her doorstep, you realize she’s the driver, not the mother.

If that weren’t enough of a jolt to the system, with the twist revealed, Mackintosh introduces a third point of view for the final half: this one in second person (as defined by me and not the purists), to skin-crawling effect. Jenna’s sociopathic, estranged husband Ian takes the stage and speaks directly to Jenna in his chapters. “You were sitting in a corner of the student union when I first saw you.” I remember breaking into goosebumps when I read his first scene and realized what was happening. Second-person narration is the perfect tone for his possessive, conniving, and blame-shifting character.

Stevens, Jenna, and Ian take the book through its climax, denouement, and unsettling epilogue. I’ve left some surprises unspoiled, so if you haven’t read this book yet, I’d encourage it!

Mackintosh deserves standing applause on this one. Not only does each POV character have a different narrative form, which makes it easy to keep them straight, but character and form are perfectly matched in each case. Mackintosh’s choices enhanced each character’s voice.

That might be a fifth question to start asking myself when I’m making decisions about narrative distance and points of view: how does my decision impact my voice and the character’s (if applicable)? This is different than my fourth question, which aims at enjoying the writing process. If you can enjoy writing the story multiple ways, which sounds right to the ear? Next month I’ll be back with more on narrative distance, voice, and my real-life mentee whose novella is nearing publication.

If you’ve worked on a novel before, have you given much thought to point-of-view decisions before you started drafting, or did you have the audacity to go on pure instinct?

This footnote contains a significant spoiler to Gillian Flynn’s Gone Girl. To call back an old piece of mine, Gone Girl’s early Amy chapters, written in first person but noted as diary entries, count as clever. Flynn told us all along that they were diary entries, and we learned at the midpoint that they were carefully fabricated and left for the police to find. It all made sense. It wasn’t Amy actually rambling in her head, lying to herself and the reader who happened to be reading her thoughts. She was intentionally lying to the reader of those pages, who, in the world of the story, was the police.

I’m trying to keep this piece from being the length of a novel, so I’m leaving “objective” vs. “subjective,” “deep,” or “close” discussions for next time.

I love this analysis and I can't wait to read I LET YOU GO. Re: 2nd person. I love how this sneakily obscures who is doing the talking, i.e. addressing the reader, or, for that matter, who is being addressed if it's NOT the reader--and, nooooo, I don't happen to be experimenting with this at the present. P.S. I wish I'd read your thoughts on epilogue a year ago. You are so right.

I didn't think I liked second person until I read Rebecca Makkai's new book.