This month’s mentor column is a little more personal and even less confident than my past ones have been. But this is what my real-life mentorships have been like: I try to be honest, even when I learned the lesson through an experience that felt like failure. Sometimes I’m teaching an answer, but sometimes I’m teaching a question. (I think that’s a truth in novel-writing: asking yourself the right questions might be even more important than how you end up answering them.)

So today, I’m sharing a question I’ve been asking myself. And unlike in my past mentor columns, I’m not talking about it through the lens of someone else’s book. I’m not even going to use my own published book as an example–I’m talking about the stories I’ve tried to write since that one.

So here’s the question: are characters real? Even though I’m the one who asked it, the lawyer in me is like, well, it depends on how you define the word “real.” And “characters.” Maybe even “are,” not to go Bill Clinton on myself.1 But I’m not going to define those words because I’m not getting deposed. I’m thinking about an art form. Fluidity in what words could mean is probably helpful.

I’ve been trying to write a second novel since I sold my first one in a two-book deal in October of 2019. (We finalized the contracts in March of 2020, and yes, I did wonder if Covid was going to blow it all up.) I remember my agent Helen asking me back in October if I had any ideas for another book. I shared a very generic premise that intrigued me; she wasn’t an instant fan, and I abandoned it without much thought. (Early lesson about myself: I am insecure and crave immediate enthusiasm.) I spent a couple months outlining another idea and pitched it to her in December 2019. No dice. I went on like that, pitching ideas, some making it to my editors but never to everyone’s satisfaction (including my own–they okayed one idea and I jumped ship for another). Soon it was March of 2021 and it was pretty clear I was not going to be on the one-book-a-year track, but my own internal pressure to produce something as quickly as possible remained.

Every time I talked to Helen about an idea for a book, somewhere in the conversation she would say something like this: Characters are real. They talk to you. The best thing you can do is follow the person who’s speaking to you.

It’s important to me that you know this: Helen has a British accent. As an American, this means everything she says sounds brilliant to me. Knowing this, I had a hard time evaluating whether I actually believed her or not. She would always qualify that her belief was “woo,” or “woo-woo”: slang for something unscientific and a bit out there.

Over the couple years of doing this with possible projects, I had different experiences. Sometimes I felt like one of my characters was talking to me, but they didn’t seem to be doing anything interesting. (Because I still needed to be writing something suspenseful: I was under contract for a book “in the same vein as” my first.) Other times none of the characters seemed real…I had a topic I wanted to explore or a scenario that sounded exciting, but the characters felt very manufactured for the purpose of telling that story. Often I felt like saying “That’s not advice! I need to write a novel now! I can’t wait for the character to be real and the plot to be interesting! Just tell me how to force it!”

In May of 2021, days after I gave birth to our daughter, I got word that everyone was on board with the last idea I’d pitched. I had characters in my head, some cool plot stuff, and something thematic I wanted to talk about. But I also had a newborn so it took many months for me to start dabbling with the book again, and by the time I was actively writing it in April 2022, it had gone through immense changes. That said, some of the structural surprises were still there, and ghosts of the old plot, and, importantly, I’d held onto one of the main characters but had new expectations for who she’d be.

I think that part’s important. When I ask are characters real, part of what I’m asking is: can you develop a character, or can you only ever discover them? Can a character refuse to be who you want her to be? And if you try to force it, will you end up with a character who reads as flat, or does things that don’t make sense, or some other bad outcome? Put another way: have you taken a real person and flattened her into something else? And if you refuse to write a flat character but also refuse to let her be who she is, what happens to the story?

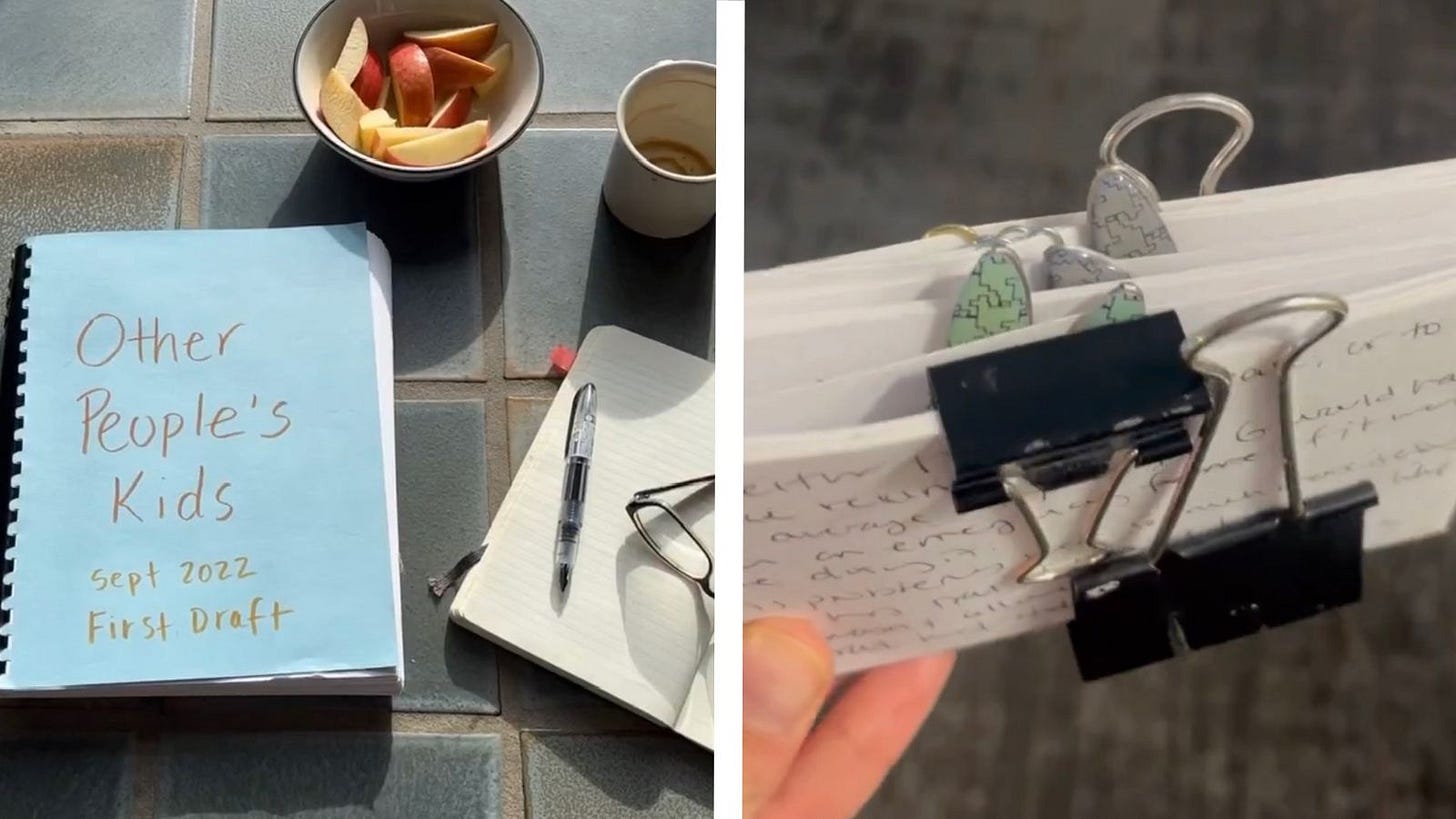

I’ve got some anecdotal answers to those questions. Somewhere in the spring or summer of 2022, I hit on something thematic that I felt a deep need to express, and I started calling the book Other People’s Kids. I had felt tied to a midpoint twist idea I’d had that everyone loved, and I was manufacturing the rest of the book around that, but I finally had something else to guide me in writing. I was fumbling towards the twist, the fallout, and the theme, writing alternating point-of-view chapters. Every time I talked to Helen about the book, I admitted what a slog it was, and she would say “someone in this book is talking to you.” Finally, I started agreeing with her. Someone was talking. I started only writing that character’s point of view, and I changed it to first person, and I had an epiphany about how the book would end. I let the midpoint twist drop, opting for a surprise at the end and a climax that was personal to the character I’d latched on to. The draft was short and messy but had the bones I wanted so I sent it to Helen. About a month went by, during which time I started dabbling with a potential third book. (More on this later.) Helen finally called. All the parts I liked weren’t going to work for my contract. It was youthful, voicey, a little light, not especially complex. I was under contract for a book “in the same vein as” my first, which had been undeniably adult, serious, heavy, and complex.

So I gave it a couple weeks (not enough time, looking back) and came at it again. I made everything more adult, more serious, worse actions, worse outcomes. This changed the characters–it had to. The old characters wouldn’t have done what I was making them do. Except I swear to you, the characters didn’t totally change. It was almost like I’d bring the same people out onstage and tell them to do something, and we’d sit there trying to figure out how it would go because I didn’t even know who this woman was anymore, if she wasn’t who she used to be.

I had very little fun writing that book. (Researching it was fun; writing it was not.) I thought I had a plot problem: I couldn’t figure out how the middle of the book unfolded, in real time, and I couldn’t decide how to reveal things structurally. But I was starting to see that it was really a character problem: I didn’t know how things unfolded because I didn’t know what these people would do in response to any given plot point.

I started journaling for the characters, answering questions about their wants, needs, desires, and misbeliefs. Many of the answers surprised me and brought me back to the old version of the book; other times I was able to get an answer that worked for this version, but when I went back into the manuscript to write I quickly got lost in the mess I had made in Scrivener. One Saturday afternoon, I laid on the floor in all my melodrama and wept, saying to Ben that I felt like the book was dead. I really meant it. I felt like, if there had ever been life in it, it was gone.

I had taken a long break from talking to Helen about the book, because I wanted to try to do it myself, but it wasn’t working. The book was a disaster, and now it was April of 2023. I felt like I was failing everyone. So I called Helen and told her how awful it was going and the problems I was having.

It probably goes without saying that this is not an actual transcript of our call, just the essence of what she said.

Helen: “I need to ask you something, and I want you to really think about it: is this even the book?”

Caitlin: “I didn’t think I could afford to ask that question.” [2 ]

Helen: “I don’t think you can afford not to. You know my woo belief that characters are real.”

Caitlin: “Oh yes, I remember.”

Helen: “And you know I always tell you to listen to the character that’s speaking to you?”

Caitlin: “Yes.”

Helen: “Well it seems to me that no one is speaking to you.”

This is the part of the transcript where there would be a lot of breaks for laughter and some expletives.3

Helen asked me about other ideas. I told her I had the start of one, which I’d worked on while she had the first draft of Other People’s Kids. I had four characters, a set-up, and no clue what would happen when the story reached a certain point. She pressed for more detail, and I gave it. I think she liked the set up, and I know she liked how I talked about the characters.

Helen said, “write that story.” She said it so confidently that it made me feel confident. “Seriously,” she said. “Walk away from this other one. Don’t think about it another day. I’m serious.”

We were both laughing, but she seemed to mean it.

I said that maybe one day my characters from Other People’s Kids would start talking to me.

“No,” she said. “In my experience, if they’re not talking to you now, they’re never going to.”

“Really,” I said.

“Yes. They don’t want to talk to you. They never asked to be created.”

She was telling me that I had brought these people into existence against their will and they resented me for it. It sounded batshit crazy, and yet it made total sense.

I started writing that new story in the last days of April. I’m around 34,000 words in. There was a very rough week in there where I wrote almost nothing, but overall I have had more fun and ease writing this book than I ever felt, combined, in the two years working on Other People’s Kids. And I can’t help but feel that the huge difference is that these characters feel very real to me and I’m letting them do what seems natural to them in every single scene. (They’ve already deviated from my plot substantially at several points, and I’ve let them.) That one bad week was when I got to the part of the story I referenced above, where I didn’t know what happened from there. Again it came down to a character issue, this time with someone outside those four characters I knew. So instead of pressing forward in the manuscript itself, I started journaling, making voice notes, writing on a whiteboard, listening to music, and thinking about who a particular character was. I made a decision (or did someone show up?) and I figured out who this person was. I got back into it and have had another solid couple weeks of writing since.

Is the book going to be worth reading at the end of this draft? Hell no, it’s a first draft. Will this book be the one that finally gets published? I don’t know. I don’t think Other People’s Kids will be my second published novel, but I also wouldn’t say we’ve fully broken up. This experience is making me want to go back to that story and write it the way it wants to be written–the youthful, lighter, straightforward way. But it sounds like it might be YA. Or it might sit in that uncomfortable space between YA and adult. I don’t know. I don’t need to know right now, because we are separated, and I’ve moved in with this new book. We’ve committed to spending the summer together.

I’m sharing all of this because I think there’s a lesson here. And I think the question is important. Like I said, it might be that just asking yourself the question is more important than how you personally answer it. If you’re writing a book, are your characters real? If they’re not, what are the implications for the story you’re writing? If they are, how are you going to work with them?

Andromeda’s latest piece talked about Elizabeth Gilbert and Big Magic, which I re-read in the first week I was working on the new novel. Gilbert talks a lot about being in partnership with creative energy and the ideas that grace you. This really resonated, in combination with Helen’s belief that my characters, all characters, are real, with a sense of identity and a stake in the game of writing a novel.

So, right now, I’m trying to give my characters better working conditions than in my last novel. I’m trying to let them be authentic to how I see them. Let them make decisions in scenes rather than change details about them to fit how I wanted a scene to end. I’m trying to discover who these people are, not develop them in order to fit a sexy twist idea. (I’ve had plenty of those, but I’ve let them go, opting instead to work with my characters.)

How will this story turn out? I don’t know yet. But I promise, I’m telling the truth when I say that the writing experience itself has been so much better for all the people involved, whether you count my characters or not.

What do you think: are characters real? And if so, do you think the characters from Other People’s Kids are going to sue me for creating a toxic work environment?

I don’t want to assume this is a universal reference because I probably wouldn’t get it if it weren’t for Mel Zarr’s introduction to civil procedure class in law school. In short, during a deposition, then President Bill Clinton was being asked about a statement that read, in part, “there is absolutely no sex of any kind” between himself and Monica Lewinsky. When asked if that statement was false, Clinton began with: “It depends on what the meaning of the word ‘is’ is.” The transcript is here; if you search the word “means,” you’ll hit the famous answer.

Remember, I’m still under contract, and I’ve never forgotten that the original hope was for a book a year. This weighs on me, even though I don’t think any of my editors want it to. Reality has never stopped me from making up my own ideas about what other people are thinking!

Fun fact: Genuinely thought the word was “explicative” until I wrote “explicatives” and Google Docs said it didn’t know what I was trying to spell.

I've had characters who feel completely whole and real, yet I still wasn't sure they'd be able to hold up a novel, and characters I did have to prod along, the poor little Frankensteins. But I spend the most time thinking about the characters I abandoned, the ones who did nothing wrong, who might have held up, and yet I dropped them anyway; I think of them abandoned where I left them, shipwrecked on a deserted island or waiting for a cancer scan to come back, trapped in both time and place, and I FEEL SO BAD.

Thank you so much for sharing your experience! As I head into another rewrite (hahahahah it's fine), I find I'm craving more stories like this where the writing process pans out differently than expected. And I agree characters are real. I only wish sometimes mine were real enough for me to tell them EXACTLY how I feel about them lol