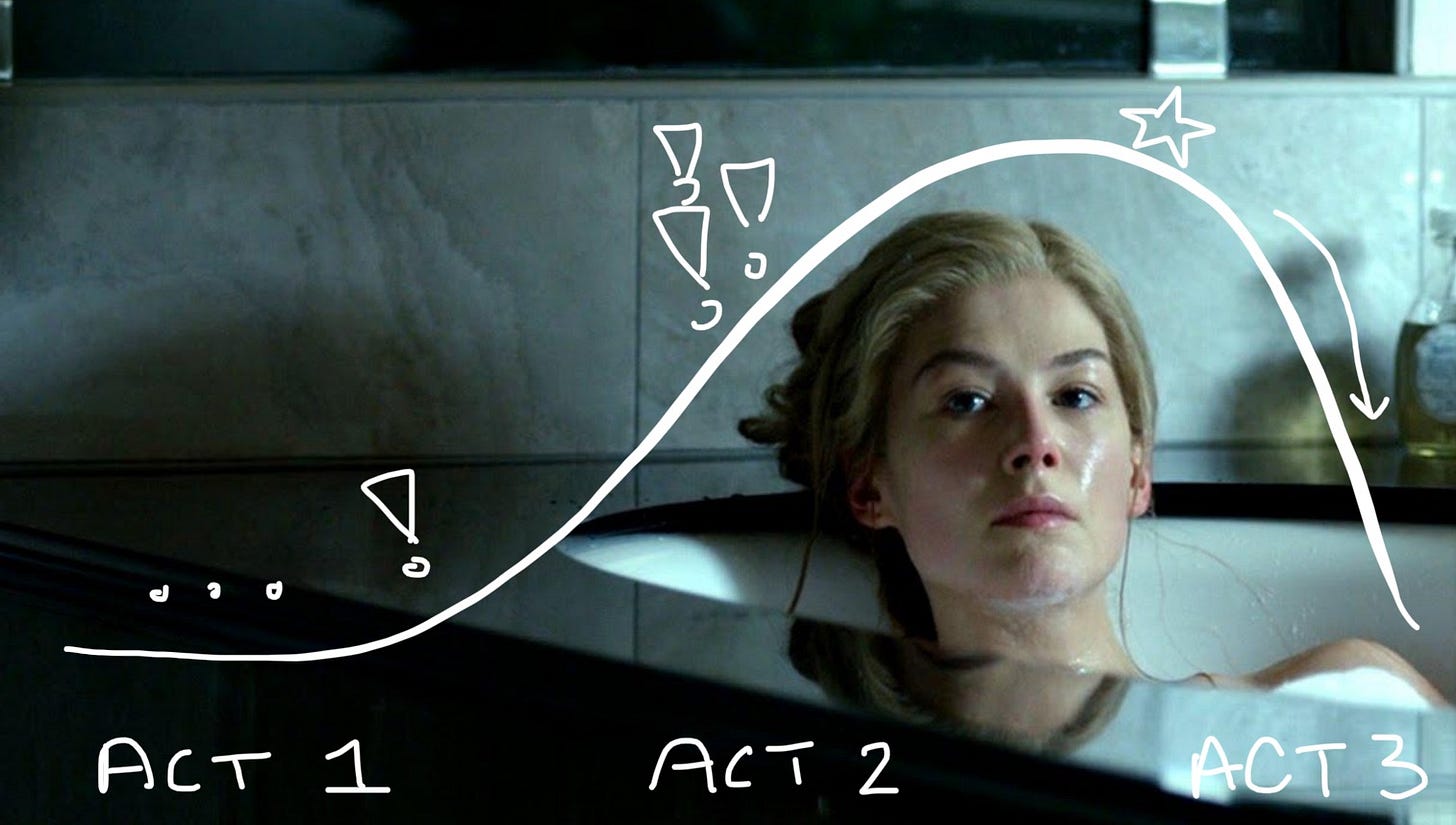

How to Gone a Girl in 3 Steps

Using the three-act story structure to maximize suspense

Last month I wrote about why I think story structure is so important when you’re writing suspense. When I’ve worked with young writers, I’ve taught the three-act story structure early on. It’s my favorite to work with, it’s easy to understand, and like many a thriller, it comes with a midpoint twist.

If you look up this structure online, you’ll find oodles of articles about it, some more prescriptive than others. If you want a formula for writing a story (and it’s okay if you do), you can find one pretty quickly by looking up this structure.1 I want to talk about it a little more permissively, more as a tool than a set of rules a story needs to follow. And, like we love to do here at Present Tense, I want to talk about suspense.

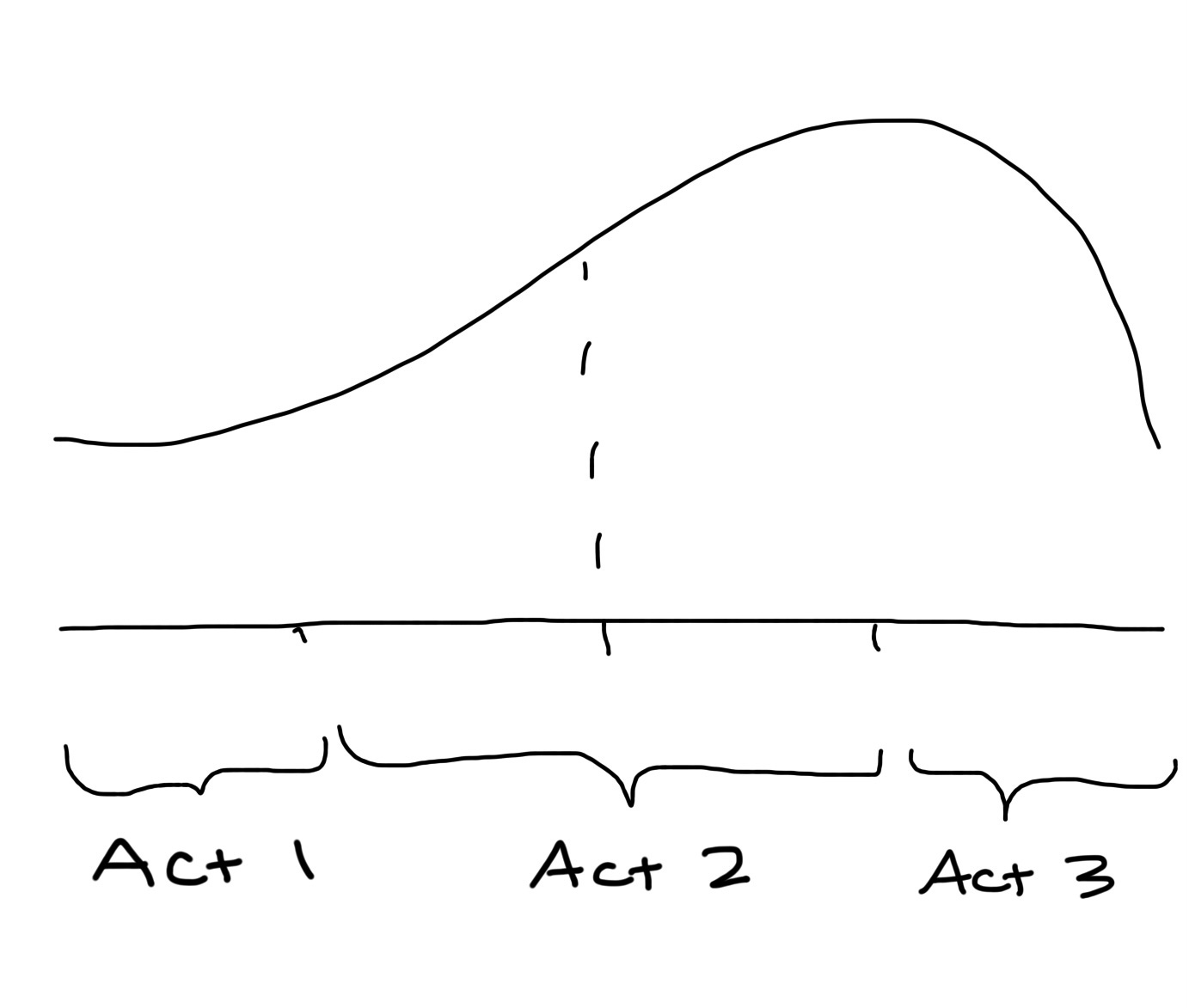

Believe it or not, the three-act structure divides a story into three acts. Act 1 is often called set up, Act 2 confrontation, and Act 3 resolution.

Act 1 is where you set up the story: you introduce the characters, the setting, and the “inciting incident” of the novel.2 Act 2 is where the characters confront the incident that has kicked off the story, face obstacles, and the action, tension, and conflict climb. Act 3 is the resolution, where you ride through the climax of the novel, any aftershocks, and, usually, into a denouement (a section of the book where the reader experiences where the characters have come to rest after the novel has thrashed them).3

As you can see, this means that Act 2 is really the bulk of the novel. So here’s that twist I promised: almost everyone agrees that Act 2 is best divided in half. That’s right–the three-act structure is really four parts! How stupid! I love it! But it makes sense. The “confrontation” of a story should take up way more space than the set up and resolution, and so dividing the confrontation in half, mentally, will encourage you to fill it up (not stretch out a handful of plot points, leading to a boring plateau the reader has to cross in order to reach the climax).

In my years of novel research, I eventually googled the words “four act structure,” which essentially yields the same thing we’ve been talking about with a clearer divide: “confrontation” becomes “reaction” and then “action,” or “response” and then “attack.”

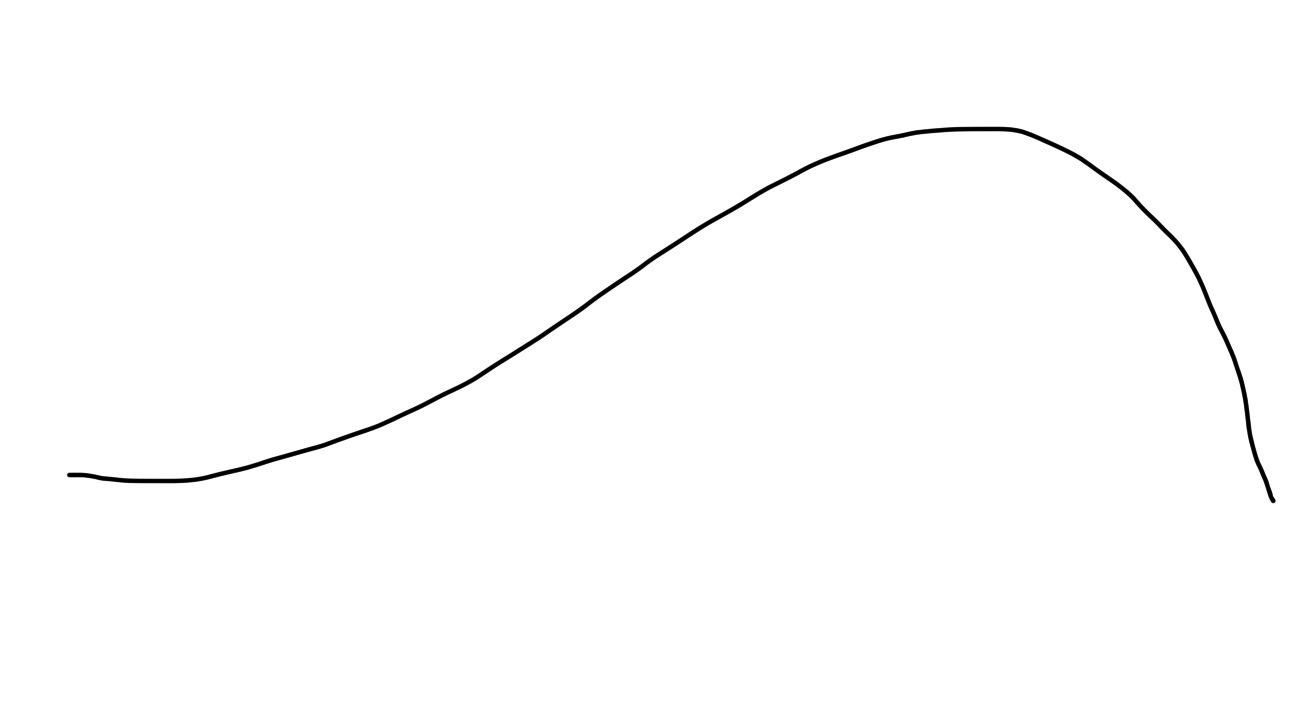

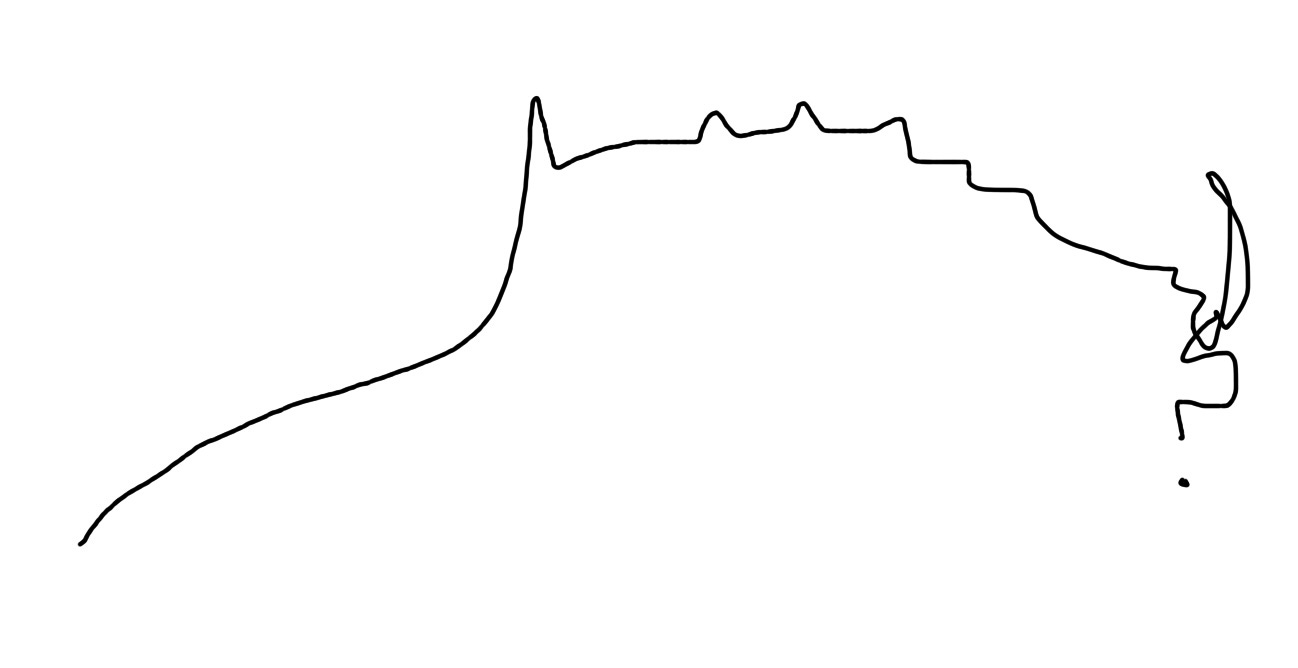

Every now and then I find it helpful to draw out the structure while I’m working on a novel–really, I’m drawing a wave of energy building, cresting, and crashing. That’s what I want a suspense novel to feel like.

I usually draw this:

Oversimple, but it gets my brain working.

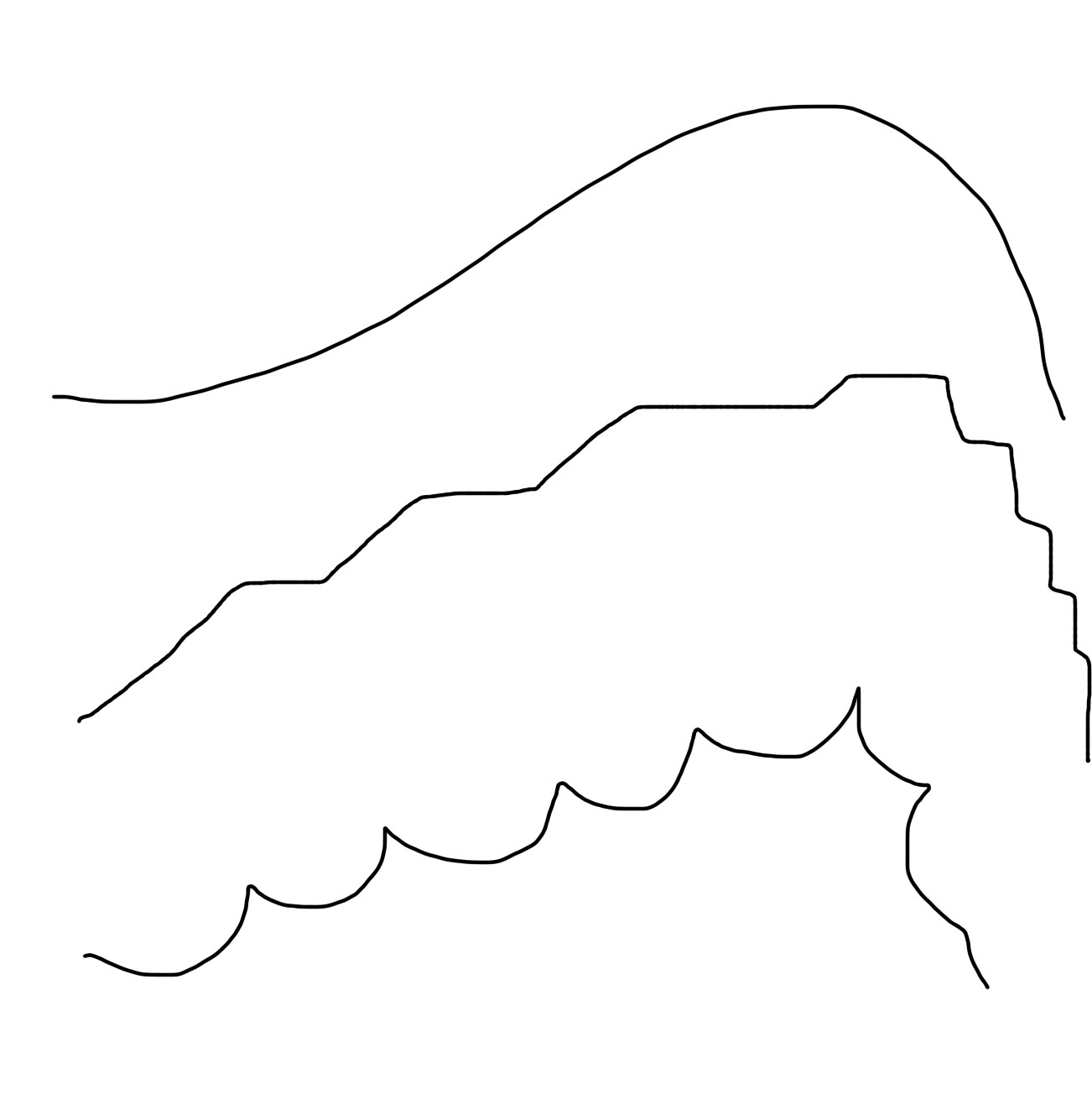

You might prefer something that accounts for breaks in the rising action—obstacles overcome and whatnot.

I tend to think of the line as the story’s energy: the characters’ stress, how much conflict is happening, how suspenseful the story is, what the stakes are, and where (I hope) the reader’s emotions are.

Going back to our main goal of keeping the reader in suspense, you can really use the midpoint of act 2 to your advantage.

Does a suspense novel require a shocking twist in the middle? No! But the midpoint is a good place to do something. For my own debut, it’s where I ratcheted up the stakes. (I had dual timelines going, and in the later timeline I revealed something big that was coming in the earlier one.) The middle of the book is also a good place to have your main character start to change from being reactive to all the shit life is shoveling at her to being more proactive.

But can it be a twist? Oh baby, yes, if you’ve got an idea for a twist, consider the middle of your story. I’m going to talk about Gone Girl below, but another famous and successful suspense novel was Clare McIntosh’s I Let You Go, which had another incredibly effective midpoint twist that McIntosh used to surprise the reader, up the novel’s stakes, and introduce a villain.

This is very unscientific and anecdotal, but I feel like I take quick stock when I notice I’ve reached the middle of a book. Woah! We’re halfway there!

I love it when an author gets me excited for the second half of the book. My unofficial midpoint check-in went realllllllll well reading Gone Girl.

Here is the shape of my experience reading that book:

So how did Gillian Flynn do that to me? IDK, otherwise I’d be out here wrecking genres, too. But let’s put on our three-act-structure glasses and look at her book. (Yes, spoilers ahead.)

First, a summary, overlaid on the structure.

Act 1 / set up: Nick Dunne, husband, is ruminating on his wife. His voice is dark, dissatisfied, and guilty. Amy Dunne, wife, speaks through diary entries, girlishly (yes, very pointedly girlishly) describing the backstory of their relationship. In present day, it’s their five-year anniversary, and Nick dreads their annual tradition: Amy makes a treasure hunt, he can’t solve it, and she feels let down by him. Nick goes home from work, finds the house empty and in partial disarray, and reports Amy missing.

Act 2 / confrontation, response, reaction: Detectives investigate Amy’s disappearance. Nick works at Amy’s treasure hunt, is pressed by the police and the public, and tries to keep his mistress (surprise?) from blowing the secret of their affair. Meanwhile, Amy’s diary describes a marriage devolving and a husband growing threatening. The police learn that financial troubles were piling up and Amy was (apparently) pregnant. The treasure hunt deposits Nick at an unused shed on his sister’s property, where he finds thousands of dollars worth of items paid for on credit cards in his name.

The scene that follows, at the story’s midpoint, is the shocker that changed the psychological suspense genre: Amy speaks in a point-of-view chapter, not through a diary entry, and it turns out that Amy is a psychopath who knew Nick was cheating and, to punish him, painstakingly orchestrated her faux murder.

Still Act 2 / confrontation, attack, action: Nick’s shed discovery has made him realize that Amy has set him up. He gets proactive, trying to communicate with Amy through the media to get her to come back to him (and save him from prosecution). Meanwhile, Amy deals with obstacles in staying hidden when she finds she’s not actually willing to kill herself (the original ending she planned). She turns to an old wannabe boyfriend, Desi, for help, and for a fall guy.

Act 3 / resolution: at the climax of the story, Amy kills Desi and “escapes” from his home, after staging more evidence to make it look like he’d kidnapped her for all this time. She drives home to Nick, where she collapses in his arms in front of the reporters camped out on their lawn. In alternating perspectives, the two recount for the reader their marital denouement (but we don’t get the sense that there will be much rest for either of them). They fake happy for the media but stew in private, Nick wanting to leave her and expose the truth, and Amy plotting to keep him with her. When Amy manages to get herself pregnant (for real this time), Nick feels like he has to stay. He tells her he pities her. Amy tells the reader in her final chapter that she wishes he hadn’t said that–she just can’t seem to let it go.

A truly brilliant novel, and it fits the structure nicely. (Flynn even divided the novel into three parts: overlaying the book’s “parts” over the structure’s “acts,” part 1 takes up act 1 and the first half of act 2; part 2 finishes act 2; and part 3 is act 3.)4

Thinking about constructing a novel, what would have happened if Flynn had wanted her shocking the-girl-goned-herself revelation to be how the book ended? In order to hide the truth, Flynn would have had to hide Amy, focusing only on shithead Nick and Amy's ever-darkening diary entries. The tone would have been depressing, all of the tension coming from the dread of "knowing" Amy would die and waiting to see if Nick would be punished. Only at the end would you have a jolt of shock and a lot to process. Even more tragic, we would have missed out on half a novel’s worth of the real Amy’s searing voice.5

By placing her awesome idea for a twist at the middle of the book, Flynn gave herself tons of new material to work with—showing us who Amy really is and giving the gone girl her own obstacles to overcome in her f’d up quest for justice.

Did Gillian Flynn draw energy graphs on old poster board while she was writing this book? My perennial answer: IDK! If she did, it friggin’ worked.

The inciting incident of a novel is what kicks off the story. Super famous suspense examples are Amy Dunne goes missing in Gone Girl or Jack Torrence gets a job at a haunted hotel in The Shining.

My inexpert take is that not all suspense novels really have a denouement–when the author attempts to stretch the conflict the entire book or there’s a big surprise in the final chapter, it can mean there’s no real feeling of a comedown or a sense of how the characters feel when the action stops.

I struggled with this in my own debut, which ends with a big reveal in the final chapter. In the chapters before the very last one, I offered my best attempt at a denouement for my main characters, but it was hard to show the readers where the characters came to rest in relation to the important information I was holding back.

She titled these three sections as such: Boy Loses Girl, Boy Meets Girl, and Boy Gets Girl Back (or Vice Versa). If you read the book a while ago, did you remember how wickedly fun it was?! I didn’t!

Essayist and memoir writer Coco McCracken wrote about buying into “the Cool Girl bullshit” as a young woman and the freeing power of Amy Dunne’s scathing monologue. I’m pretty sure Coco’s letter is what put Gone Girl back in my brain while I was working on this Substack piece.

I love the diagrams! Gone Girl is a book I don’t mean to keep loving (and mentioning) but any time I pick it up for a partial re-read, I’m struck by it’s excellence.

OK. Let me see if I got this. 1) Set up the story 2) Conront the incident and face obstacles 3) resolve where the characters have come to. Thanks. I needed that