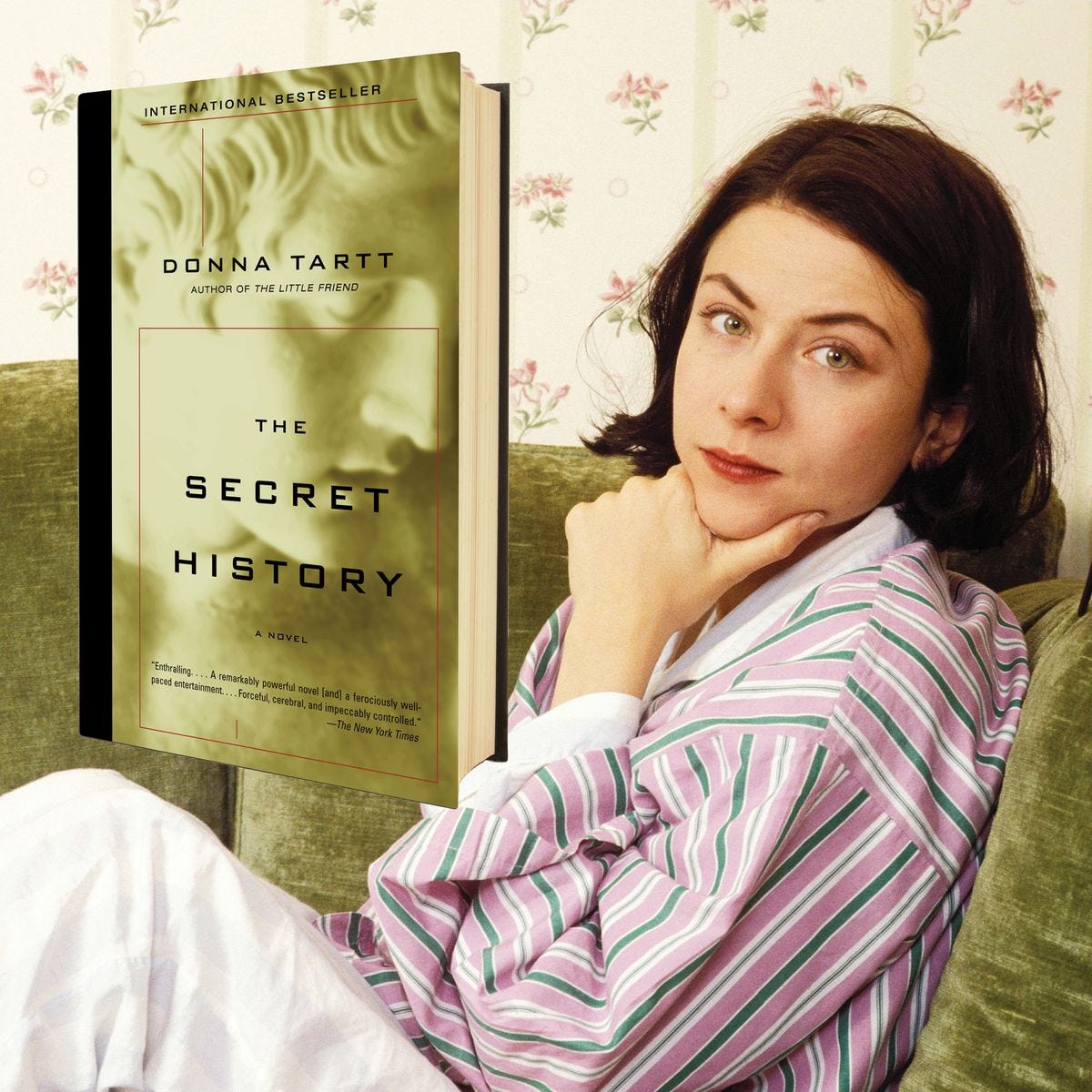

I read Donna Tartt’s The Secret History last winter (and I highly recommend it for this time of year). Since then, I’ve wanted to try a piece about how Tartt managed to build and maintain suspense in a 600-page book that gives away the midpoint murder on page 1. As I wrote the piece, the driving question became this: does Tartt build suspense in spite of this teaser…or because of it?

Absent what’s disclosed in the book’s prologue, this is actually a spoiler-free piece. If you haven’t read The Secret History but would like to eventually, I think you can safely read this without spoiling the reading experience, but, as ever, make your own choice here!

(I could not find a screen grab of the lyric I wanted—“I can’t be held responsible”—so we have to settle for the whole song, and yes you should listen because it’s as good as you remember, and also it encapsulates how I would feel if I knew I spoiled a book for you.)

Tartt’s dense literary suspense begins with a prologue, and I’m going to start there, too. Here are The Secret History’s opening lines:

The snow in the mountains was melting and Bunny had been dead for several weeks before we came to understand the gravity of our situation. He’d been dead for ten days before they found him, you know. It was one of the biggest manhunts in Vermont history–state troopers, the FBI, even an army helicopter; the college closed, the dye factory in Hampden shut down, people coming from New Hampshire, upstate New York, as far away as Boston.

It is difficult to believe that Henry’s modest plan could have worked so well despite these unforeseen events. We hadn’t intended to hide the body where it couldn’t be found. In fact, we hadn’t hidden it at all but had simply left it where it fell in hopes that some luckless passer-by would stumble over it before anyone even noticed he was missing.

In those first six sentences, Tartt has given us a victim, a mastermind, and an involved narrator. By the end of the prologue, she has deepened the reader’s understanding that this was no accidental death: in flashes of memory, Richard recalls Bunny’s question–“what are you doing up here?”–when he, “surprised, . . . found the four of us waiting for him.” Richard recounts the four of them “whispering in the underbrush–one last look at the body and a last look round, no dropped keys, lost glasses, everybody got everything?” All this by page 2 of a book that would stretch more than 600 pages; the real-time account of Bunny’s death doesn’t take place until page 303, at least in my copy.

And still, I think most would agree that The Secret History is an effective work of suspense. How does Tartt give it all away without spoiling the reading experience? Writing this piece made me realize there was an assumption built into my question: I thought she was a magician who managed to build tension in spite of her prologue…instead of thanks to her prologue. That’s how this piece turned into an ode to the well-done prologue in suspense. Because the prologue in this book was an astoundingly good idea. Without it, I wonder if it would even be considered a suspense novel (okay, it would have been, but the first 200 or so pages would not have been very suspenseful at all).

If you’re thinking…Caitlin, why do you seem surprised that a prologue was so great? Because in all my writing classes and conferences and dicking around on the internet, I have taken away the clear message from others that prologues are risky business in modern suspense. Not a do-not-enter situation, but definitely proceed-with-caution.

I’ve heard so many reasons not to write a prologue: they’re overused in suspense; they’re cheap or lazy; there’s nothing worse than going from a promising prologue to a sluggish first chapter; and so on. And yet some of the best suspense writers have used them to great acclaim. You may know the opening line of Rebecca’s, even if you’ve never read it! I think The Secret History is an example of when and how to do a prologue, and yes I will elaborate.

Tartt’s prologue sets the tone and introduces voice

You all know I love structure, so let’s start there. One simple but effective thing Tartt’s prologue did was anchor the reader in the story’s structure. In the prologue, Richard speaks from a point in time after Bunny’s death, in a manner where he is clearly telling a story. In chapter 1, Richard continues like this, starting with a history of himself and his education but with an eye toward “the story I am about to tell.” In this way, the prologue does not feel like a scene taken out of order for the purpose of promising excitement later,1 but rather the introduction to the way Richard will tell his story.

The prologue also introduces some of Tartt’s style and Richard’s voice, which is hauntingly unaffected yet conversational, even intimate. That “you know” at the end of the second sentence, for example. The push and pull of these tones provides some of the story’s emotional tension and is key to the reading experience. Similarly, the prologue introduces Richard’s suspense-inducing habit for foreshadowing, which he does throughout the book. This is one of Tartt’s tricks for maintaining the suspense she introduces in the prologue before the characters start actually feeling the pressure to kill Bunny. (As the story ramps up, so does the suspense, and foreshadowing becomes less necessary.)

The prologue puts the bomb under the table

Thinking about the prologue and the 300-page climb to Bunny’s murder reminds me of the Alfred Hitchcock interview Andromeda and I love.

By Hitchcock’s reasoning, Tartt enhanced her audience’s experience of suspense by revealing the bomb under the table (Bunny’s eventual murder) so that we’d all be squirming in our seats waiting to see it go off. (And, as noted above, Richard’s penchant for foreshadowing continuously reminds the reader of the bomb.) And even more brilliantly, so much of the story is about why someone put a bomb under the table in the first place: how were these characters going to come to the place that they killed someone?

Without the prologue and the foreshadowing that calls back the prologue, the early tension in the story is all interpersonal. Will Richard be accepted into the fold of the enigmatic Classics professor? Will the little cult of students accept him? Without the prologue, there isn’t much suspense, by the average suspense reader’s use of the word. With the prologue, there is exquisite suspense. Every time Bunny is on the page, I am alert. Am I going to mourn his death? Or maybe he’ll become a villain I’ll want to see die? What on earth is he going to do to make these rich, preppy nerds kill him??

The prologue also tells us who puts the bomb under the table (…or does it?). Richard calls himself “partially responsible” but implies that Henry is the ringleader, calling it “Henry’s modest plan” and describing him as a father-like figure driving the rest of them home from the scene of the crime. Tartt uses the prologue to point out an important character to watch for our mystery-solving pleasure. But of course, she does not reveal all the people worth watching–Henry is not the story’s only villain, or perhaps even its mastermind. A successful suspense writer knows how to direct the reader’s attention, as well as misdirect it.

The prologue is just good, okay?

Her writing is hypnotic.

Though I remember the walk back and the first lonely flakes of snow that came drifting through the pines, remember piling gratefully into the car and starting down the road like a family on vacation, with Henry driving clench-jawed through the potholes and the rest of us leaning over the seats and talking like children, though I remember only too well the long terrible night that lay ahead and the long terrible days and nights that followed, I have only to glance over my shoulder for all those years to drop away and I see it behind me again, the ravine, rising all green and black through the saplings, a picture that will never leave me.

And this gorgeous writing is not a promise Tartt can’t deliver—she maintains her skillful prose throughout the novel. (Nothing worse than falling in love with the writing in a prologue only to find the book doesn’t match!)

What Tartt wrote was great, and what she didn’t write into the prologue was great, too.

Importantly, Tartt resists info dumping in the prologue. She doesn’t go on about Hampden, or Julian and his Greek class, or Richard’s background, or actually name any people besides Bunny and Henry. (She doesn’t even name Richard!) She is super controlled in what information she disperses, all of it precisely what she wants the reader to focus on.

And she only shows snippets of the moments surrounding Bunny’s death. His surprise when he finds the others waiting for him. Their conspiratorial whispers after. If she’d written the actual scene of Bunny’s death in the first two pages, I bet it would have fallen flat. The reader would have no emotional connection to Bunny, nor Richard, Henry, or the others involved. No sense of who these people were and why they were doing something so monstrous. Instead, Tartt said: these people you’re about to meet are going to do something monstrous…interested? Then she spent 300 pages building the story until the moment finally came.

Have you read The Secret History? Anything else by Donna Tartt? I own The Goldfinch but can’t bring myself to try it…it’s just so damn long. Am I missing out?

I’m not saying this is necessarily a bad thing to do in a prologue; it can be done effectively. Examples I can think of that worked for me were those where the prologue actively showed a standalone scene that would be understood one way on first read and a second way later in the book, such as in Clare Mackintosh’s I Let You Go or Andromeda’s upcoming The Deepest Lake.

I haven’t read this book. I should! I know!!! But about prologues. Such an essential discussion for we contrary-ites! I’m thinking of one podcast that is so useful except that the hosts give anti-prologue advice too often when the truth is that many good suspense novels use prologues and I’m not convinced agents and editors dislike them as a rule.

This prologue is one of the single greatest pieces of writing I have ever read. Granted I’m not that wonderfully well read on say, allll the classics but still. That’s saying something