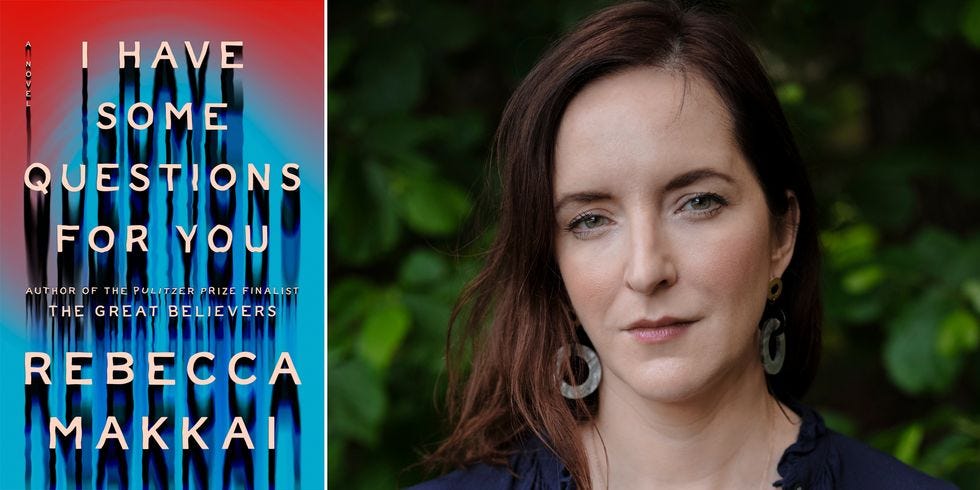

The One with Some Thoughts on Voice (re: I Have Some Questions for You)

In which we have no questions for Rebecca Makkai but will gladly compile thoughts from interviews she has given elsewhere, in order to discuss a tricky writing topic.

I wasn’t in a special hurry to read Rebecca Makkai’s I Have Some Questions for You, which claimed NYT bestseller spot #3 this week. The premise—A film professor and podcaster is invited back to teach a course at the boarding school where her roommate was murdered—didn’t grab me right away1, in part because I’ve recently read several thrillers which incorporate podcasts2 and establish critiques of our cultural fascination with true crime.

But something happened to upset my TBR ambivalence. That something was voice, the subject of this post.

My husband read the novel’s first paragraphs to me from an article he was perusing, refusing to listen that I’d already bought too many books in the last week alone. (If it’s not clear, YES, I did buy Makkai’s latest. My hubby and I listened to it together, via audiobook, during a spring break road trip.)

The part that first grabbed my attention also grabbed Washington Post reviewer Ron Charles. He quoted the opening of I Have Some Questions for You this way:

It begins with people trying to remember which murdered woman they’re talking about:

“Wasn’t it the one where she was stabbed in — no. The one where she got in a cab with — different girl. The one where she went to the frat party, the one where he used a stick, the one where he used a hammer, the one where she picked him up from rehab and he — no. The one where he’d been watching her jog every day? The one where she made the mistake of telling him her period was late? The one with the uncle? Wait, the other one with the uncle?”

Variations on this riff are repeated elsewhere in the novel, creating an efficient critique of the way we flatten crime victims into a half-forgotten series of predictable tragedies, potentially numbing ourselves to the true horror of crime and the plight of its victims.

Makkai also makes spare use of an intriguing second-person address—first cryptic, later clarified—that gains in importance as the novel proceeds.

Those and other features—interesting POV choices, repetition, and the creation of a candid, first-person narrator voice that seeks to comment, ruminate and excavate, not just turn simple plot gears—are only a few elements of Makkai’s authorial voice or style.

To these, we could add freshness of description, including images filtered through memory. Here’s our narrator, Bodie Kain, thinking about the former high school where she has returned to teach.

“I’d forgotten about the light at Granby. Outside, in winter, it came down in needles; inside, it fell like soup.”

Light as needles. Light as soup.

A chatbot wouldn’t have written those lines. As some of us have been musing lately, the one thing chatbots can teach us is how to lean into the elements of writing that AI won’t easily master, because AI—for now—excels at bland, unoriginal prose.

Strong voice in a commercially successful suspense novel is exhilarating. I’ll go out on a limb—hoping you will disagree with me—and say that it is also somewhat rare.

This issue came up in one of my writing groups recently, when a participant asked the rest of us to help identify her voice.

The problem is, voice is hard to identify, especially when it’s your own. That’s the main takeaway I got from reading Ben Yagoda’s The Sound on the Page, a deeply researched analysis of authorial voice and style, many years ago.

As Yagoda told an interviewer when asked about one of his book’s biggest surprises,

I interviewed more than 40 people for the book — authors as diverse as Dave Barry, Bill Bryson, the poet Billy Collins, Cynthia Ozick, Susan Orlean, Andrei Codrescu, and Supreme Court Justice Stephen Breyer — and only a handful, I would say, could articulate a really strong sense of their own writing style.

But of course, we can’t describe our own spoken voices easily, either.

As writers, do we need to pay conscious attention to our authorial fingerprints in order to develop style on the sentence and paragraph level? Or does voice and style emerge most naturally from our choices of subject, our reading habits, and our individual backgrounds, just to name three contributing factors?

Some of us define voice or style3 narrowly, focusing on things like diction (word choice) and syntax. I define voice more broadly, encompassing what the author chooses to pay attention to, even before that way of seeing the world is filtered down to the word and sentence level.

Either way, I believe—and I actively worry, to be honest—that the required plottiness of suspense sometimes flattens our language and makes us more susceptible to cliche.

My shaky hypothesis is that we do so much work trying to direct the reader’s attention both toward and strategically away from what’s happening in the story that we simplify language and default to common phrases and overworked gestures. (Hearts beat quickly, chests tighten, faces flush too often; I’m guilty of all these generic physical descriptions and more.)

The result is that too many suspense novels read alike, due to unexceptional language as well as similar plots emphasizing a limited number of story options—the husband did it; the friend did it; the narrator herself did it.

Recently, I was disappointed to realize how easily I was forgetting many of the mysteries and thrillers I’ve read in the last two or three years. Granted, my memory is spotty in general. (Terrible memory may even be my superpower!)

But I don’t as easily forget the non-crime, purely literary novels I’ve read4. Each one is its own odd little project, and I may love a literary novel or dislike it, but I probably won’t confuse it with five other books on my nightstand or Kindle.

Is there a solution for suspense writers who would like to write more distinctively? (Aside from, Write four literary books of varying subgenres before you plunge into writing mysteries or thrillers.)

We could ask Rebecca Makkai, but hey, she’s on a book tour! Here’s a distillation of good advice I’m sure she’d be willing to share with us all5:

Read well beyond your comfort zone

Makkai reads broadly—nonfiction on very specific topics, plays, poetry—and she also reads beyond borders. As she told the New York Times and writes about in her Substack, the author has been reading her way “around the world with 84 books in translation, as a memorial to my late father — a poet and literary translator who died in 2020 at the age of 84. He was Hungarian, and so I started in Hungary and will end there too.”

Research, see the world, and do the work

No thesaurus can substitute for getting out in the world, observing, learning, rejecting received wisdom, and facing one’s own ignorance. Makkai has written about the vast research required to write her last book, The Great Believers, a novel set in Chicago about the AIDS epidemic. In this especially good interview, she explains how she almost made a specific description mistake—having a character peer into the windows of gay bars looking for friends—only to correct herself based on research, which informed her that gay bars of that era had blacked-out or curtained windows. (Aside from researching details, this interview includes a great discussion about writing “across difference,” i.e. characters who are not like you.)

Listen to audiobooks

When I read books, I sometimes find myself reading for story more than language, but when I listen to audiobooks, individual phrases and sentences jump out at me—perhaps because my listening speed is slower than my reading speed. (Reading a physical book and then following up with a successive audiobook version can be an extra helpful way of noticing new things about a favorite writer’s style.)

I was charmed, therefore, to discover that Makkai is also an audiobook fan, though in her case, she doesn’t use that format as a way to slow down. As she told the NYT,

“I increasingly listen to audiobooks, at about 1.7x speed or higher. Walking along the Lake Michigan shore with a coffee in my hand and someone talking manically in my ears is just about perfect.”

Embrace your worldview

How you see the world affects voice as well, including elements like tone. After publishing her short story collection, Music for Wartime, Makkai told the Baltimore Sun,

“I find a lot of things disturbing and I find a lot of things funny. … For better or worse, that’s the way I see the world. The times I’ve tried not to be funny it’s never worked, and the times I’m trying not to be dark and just be funny, that never works, either. As varied as my subject matter is, I think the worldview is pretty consistent: seeing darkness and seeing humor.”

Do you have favorite suspense authors whose voices are especially distinctive? What makes them so? We’d love to hear!

Yes, it would have grabbed me in the next few months, once I kept hearing from friends that I Have Some Questions for You is a great read. I predict word-of-mouth for this book to invite comparisons to the ever-mentioned Gone Girl (based not on plot but other aspects of craft) or Danya Kukafka’s more recent Notes on an Execution, which asks some similar questions about society’s fascination with true crime.

For crime thrillers about podcasts, see this roundup, which includes some good ones!

And what is the difference between voice and style, anyway? You can use them interchangeably if you are a lumper. If that seems like a cop-out, dig into the subject by reading Ben Yagoda’s book.

Like which literary novel, you’re asking. The Netanyahus by Joshua Cohen, winner of the 2022 Pulitzer Prize and a pretty darn funny and definitely original campus novel, comes to mind.

And if Rebecca Makkai herself ever reads this and comments—perhaps by offering up additional voice/style advice—I will be over the moon.

I loved this so much Andromeda. I’ve been thinking about “voice” a lot TOO lately! And, in my own experience, playing with my voice but not getting “voicy” 😵💫

I loved this book and the audiobook in particular so much. I bought a physical copy too and am looking forward to rereading.