Yes, I *do* think you should write a suspense novel

Why it's harder than many think; why it may be good for you as a writer

Six years ago, I started writing suspense fiction. I had a false start with one manuscript, then learned from my mistakes and wrote another. This new idea proved easier to write and sell, but just when I thought I’d figured out how suspense works, I was tested by revisions. So many revisions! (I received notes from three agents and two editors; I ended up writing two different versions of the same book. Other posts about revising suspense here and here and here.)

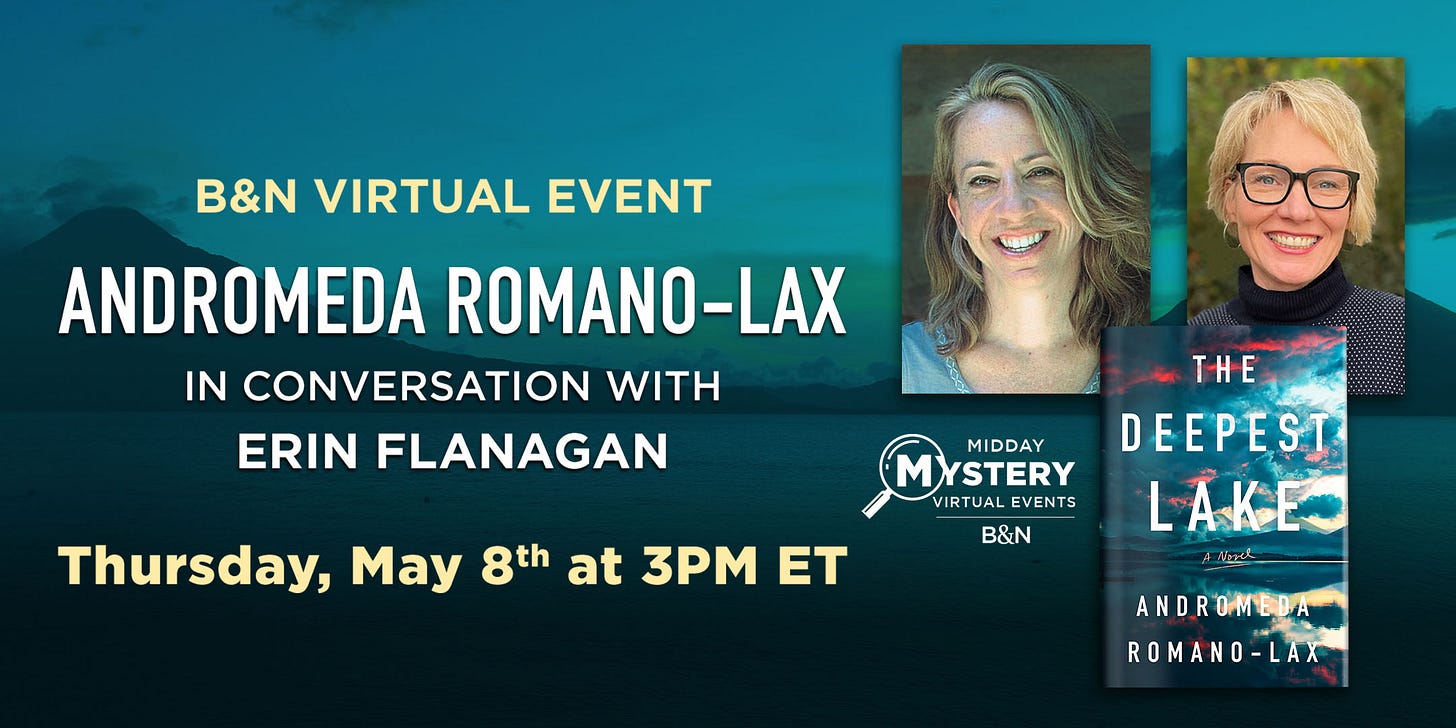

Four years after I pitched its plot to an editor, The Deepest Lake was finally published. A paperback edition comes out in two weeks! (Please come to my Barnes & Noble mid-day event on May 8 with Erin Flanagan; see bottom of this post or click here to register.) And now I’m finishing line edits on a second suspense novel called What Boys Learn with a pub date in early 2026.

Six years. Two books. Literally hundreds of drafts.

I thought it was time to share what I’ve learned along the way, in case you are a “suspense curious” writer. My argument here is not only that you can write suspense (or mystery/thriller/crime—call it what you will1)—but also that writing in this genre can make you a better writer, period.

Before the big promises, however, let me address two myths.

Myth #1: Suspense is easy to sell.

As someone whose early books were shelved as “literary fiction” and as a book coach and friend of literary writers, I can tell you: people from the literary side assume that genre books—crime and romance, especially—are easier to sell. They’re not.

It’s an attractive and resilient myth! The last time I was in an airport bookstore, looking at the suspense titles lined up on the limited shelf space, I thought, “Good lord! Half of these books are suspense! This must be where the easy money is, baby!” (If the money were really so easy, I would have been on my way to Fiji instead of the AWP conference in Los Angeles.)

Problem is, a lot of other writers are chasing the same money. The same crime-friendly agents. The same audience. The same tropes or structures or angles. The same cover images and fonts! It’s a crowded market.

But let’s say you want to write something that isn’t same-same-same. You’re a reader of Present Tense, after all, so I know you’re special. Your suspense novel will include issues of class or race; you’ll be making cultural commentary; you’ll be holding a mirror up to society; maybe you’re adding bits of magic or history or some other cross-genre element; maybe you’re telling your story backwards; maybe you’re doing a complex homage to another book or film.

Good! I want to read that!

Even so, it’s tough to break in, and just when you’re ready to do something edgy and complex, an editor will tell you, “Do all that and give us a character we can root for and give us a killer twist. We want it allllllll.” And the folks in marketing need to love it, too.

(Also: could you possibly be cute and funny and well-connected to all the right people?…Okay, no editor has asked me to be any of those things, although I have been told it’s professionally useful not to be a “pain in the ass.”)

Myth #2. Suspense is easy to write.

Mysteries and suspense are plotty beasts that attempt to keep the reader engaged via what is hidden or unknown, while not losing the reader along the way. Creating multiple levels of mystery without creating confusion takes a surprising number of drafts and—in my experience, reinforced by conversations with other writers—a lot more feedback and iterative editing.

Whether suspense writers are plotters, pantsers or something inbetween, they often talk about 1) not knowing or changing their minds about the most essential parts of their plots, like who committed the crime (see, Jewell and Flynn in this post) and 2) planting lots of red herrings and subplots that don’t bear fruit and have to be trimmed away later. The more complex the plot, the more often authors have to discover along the way—even if they started with an outline! (And many don’t. But if you’re a newbie, I’d recommend trying both ways.)

“This was really weird and I didn’t entirely get it” can be a three- or four-star reader review for a literary novel.

“I didn’t get it” in the world of suspense often means two stars, one star, or my recent favorite, “a one star for this book would be generous.” (I hope you’re not reading this, PattyAnn.)

Suspense has depth and ambiguity too, of course, but readers come with more expectations. They’ve often read a ton of mysteries or thrillers before reading yours. They have narrow comfort zones when it comes to pacing. (“Slow burn” is often a mixed compliment.) They want to be surprised but they also want to receive enough clues to participate in guessing what’s coming next. There are some things they want to be sure about. There are some kinds of endings they detest.

It’s hard to please readers and write something fresh and thrilling and substantial. But it’s also fun. Here’s why I think you should give it a try.

In crime fiction, character wants are clearer

As a book coach and former MFA instructor, I can tell you that most apprentice novels feature characters with unclear wants. Even after doing full revisions of full manuscripts, some writers still can’t articulate their main character’s desire. That muddiness leads to dull plots (or none), aimless conversations, an absence of clear conflict, and a whole lotta not much happening.

In suspense, the primary want is easier for both writer and reader to grasp. Characters often want to know the truth behind a crime (the who, how, or why of the “dunnit”) and/or they want to evade a present peril (someone threatening or stalking them). They want answers and they want to survive. Truth! Survival! Truth and survival. Them’s are good stakes.

Don’t get me wrong. Characters also want (and more likely, need) other things—for example, to understand themselves and others, or to find purpose or meaning, or to uncover deep emotional truths that go beyond the mystery presented in the early chapters. But the crime/suspense “want” helps move the story along, often with an emotional or psychological storyline swimming along just as urgently, under the surface.

A person in a literary novel may want to find purpose or clarity…somehow, at some point. (By staying in bed for a year? By musing quietly while killing lots of mice at a nunnery? Name those novels! Answers in footnote2.)

A person in a crime novel wants to know who the murderer was and/or needs to evade the scary person who just sent a threatening email…not “at some point.” Now!

If you are someone with a lot to say about human behavior or the nature of reality or something else, or you just love language but you can’t make a story move, I’d recommend stitching a credible crime into your plot. It won’t just give your manuscript tension, which is desirable. It will give your story a clear question—which is an engine. (And sometimes a horse.)

Crime novels make the best Trojan horses

Because a crime creates definite wants and clear questions from the outset, it can pull along a lot with it. Or to change the metaphor, it can hold a lot within it, Trojan horse-style. It has room to fit ideas, authorial fascinations, and entire worlds replete with esoteric specifics. Angie Kim’s Happiness Falls is the story of a father’s disappearance and a son’s possible culpability. But it also holds space for a wealth of information about what it’s like to be or raise a nonverbal child. On top of that, there’s room for biracial Korean-American culture—and much more.

Suspense teaches us to embrace emotion

My first two (literary) novels were about semi-opaque characters who kept their emotions hidden whenever possible. Okay, maybe my third novel as well. Gah!

My literary tastes were fed on books featuring unreliable narrators, self-saboteurs, tight-lipped existentialist types, melancholic souls, and big thinkers. These were not characters who let themselves feel very much, or at least not until each novel’s final chapters. “Too little too late” was probably my character trademark when writing realistic fiction, but then again, my favorite book used to be Remains of the Day.

Then I started writing suspense. My initial premises have all come directly from my own anxieties—more specific anxieties (like one’s child dying, or discovering a family member has committed a crime) than the more distant and intellectual anxieties I’d previously mined.

From Master Hitchcock I learned that suspense is all about emotions. (Well, if he says so!) I learned to let my characters grieve, be afraid, and get angry on the page. I am still learning how to show those emotions without using too many cliches—one’s heart can pound only so many times—but at least I know that the emotions themselves aren’t the problem. Readers want to feel. Heck, I do, too, more than ever. There’s nothing wrong with that.

Mystery is friendly to hybridization

If you’re a “can’t stay in one lane” writer like me, you will appreciate that crime novels pair well with historical fiction (crime in the past!), speculative fiction (crime in the future or in some strange world that isn’t our own!), experimental fiction (reality is in question but there is still a crime!). Horror can meet suspense and make a baby, and no one thinks that baby looks weird. It just looks like an exciting horror novel—perhaps with a killer twist!

A suspenseful thriller can be a contemporary political tale, but it can also be a serious retelling of a classic text, like James by Percival Everett. (Not a suspense novel or thriller, you say? I just attended a book club in which readers described wanting to say, “Run! Run!” to the characters; two women couldn’t sleep after reading it.)

Crime fiction has a long, rich history

The best way to learn to write—or to become a more successful writer—is to read with purpose. Crime/mystery/thrillers have been popular for hundreds of years and they have been written about for nearly as long. (See, The Life of Crime, a chronological analysis.) Between reading suspense novels and reading about suspense novels (and watching movies, too!) you have a fairly ready-set curriculum. What you probably won’t find—at least I haven’t—is a really great craft book about suspense. I can’t tell you why. Maybe it’s one reason Caitlin and I keep writing this Substack.

In closing

There’s my argument. What are you waiting for? No, really. What are you waiting for? Because if there is some aspect of craft or process or self-doubt or publishing confusion that’s got you stuck, that’s a new blogpost we can write for you! We’d love to do it. Comment below!

And oh yes. The author must promote her events! This may be the most important event I do all year, because B&N have been very supportive of the paperback release of The Deepest Lake. Come meet me and Edgar winner Erin Flanagan, who has written for Present Tense and is a funny, charming person who knows a ton, online at B&N! When you register you can submit a question in advance for either of us and I really hope you do.

I personally think suspense, mysteries, and thrillers are each structured differently and prioritize different pleasures for the reader, but I’m a splitter, not a lumper. In this post I tried to lump as much as I could by using terms mostly interchangeably.

My Year of Rest and Relaxation by Ottessa Moshfegh. Stone Yard Devotional by Charlotte Wood. Both highly respected and garlanded and yes, I read them both and found them interesting! Would they have been even more interesting if the bed-rot narrator in MYORAR had killed a person or if the mice-killing lady in SYD had fled a crime scene prior to showing up at the nunnery? Maybe!

I cannot tell you how much I loved this piece. I giggled aloud many times and kept feeling this surge of inspiration to work! To write! To feel at peace with the RE-write! To send a threatening email to PattyAnn!!

Such a great post, Andromeda! If I wasn’t already writing suspense, this would’ve convinced me to give it a try. And yay for the B&N event! So exciting! I’m so glad it’s virtual so I can join in.