Search for a True Locked Room Mystery

Deep in subgenre details thanks to The Life of Crime and googling; plus, a Nordic classic LRM rec at the end!

I work alone in a quiet house on a small island (which happens to be off another island) served by occasionally unreliable ferry service. My life is a locked room, in other words.

Or it would be, if I were murdered inside my locked house, with my house keys in my hand, and all the doors and windows sealed. An impossible crime, in other words.

That is a locked room mystery, my friends.

Tuesday night I stayed up well past midnight trying to find a locked room mystery to binge-read in order to write this post, and instead discovered to my utter frustration that people confuse closed circle mysteries1 (limited number of suspects trapped in a limited location, no need for the murder to be “impossible,” but who did the crime?) with true “impossible crime” locked room mysteries.

Late into the night I googled one book after another, reading synopses and reviews, ready to buy and start reading, getting excited…only to find out, for example, that…

The 7 Deaths of Evelyn Hardcastle by Stuart Turton, which involves time travel and body swapping as well as a difficult-to-solve crime, may be a really cool book (TBR!) but is not, in fact, a locked room mystery. Tell me if you’ve read this one!

The moody, isolation-dependent Lucy Foley books—The Guest List and The Hunting Party –are not locked room mysteries.

Ruth Ware’s books, such as In a Dark, Dark Wood, are almost but not quite locked room mysteries.

This is where I’d love you to correct me or at least weigh in. I haven’t read the books above! Let’s make this a conversation.

Ware, who was directly inspired by Agatha Christie, admirably clarifies on her website that her books are metaphorical locked room mysteries, with a limited stage and cast.

Ware explains the appeal of the subgenre beautifully:

As a reader, I think it’s just the sheer satisfaction of trying to solve the “impossible” puzzle. It’s like watching a magician pull off a conjuring trick – you’re shown something that shouldn’t be possible, a dove from thin air, a woman sawn in half, and you have to work out how it was done.

As a writer, of course, it’s fun being on the other end of the puzzle, pitting your wits against the reader to pull off your “impossible” illusion. But there’s also something really satisfying about working with a small cast of characters, and having to use them effectively. There’s no possibility for walk on parts, or convenient extras who can provide the skills or knowledge needed for a particular reveal. You have only the characters you gave yourself at the start of the enterprise, and you have to make sure they have everything you need to get you through to the final revelation. The bonus of course is that you can get to know them really well.

Sounds like fun! Why don’t Ware and book reviewers just call Ware’s books “closed circle” mysteries, then?

“I think you’re getting in the weeds here,” my husband said on Wednesday morning, when I had trouble getting out of bed.

He was home from work due to a blizzard that blanketed our island in deep snow. More seclusion! The electricity could go out at any moment! If only there were a murder! (Not really.)

Brian was drinking coffee and chuckling with appreciation as he read The Other Black Girl, which I would have loved to read with him on this snuggly morning if not for the fact that I needed to read a real locked room mystery, stat!

In response to my groaning, he agreed that I have somehow managed to turn the world of crime fiction into a type of DIY graduate degree, forcing myself to read textbooks like Life of Crime (yes, but only because I promised readers of this newsletter!) and figure out things that probably don’t matter much. It’s a pattern of mine. When I did my first graduate degree, in an esoteric field called Marine Affairs, I spent weeks trying to figure out the precise differences between self-regulation, self-management, and co-management of fisheries. Those are some dull weeds to get into. Or seaweeds?

Crime by the Book blogger “Abby” would agree with my husband that I’m making things harder than they need to be. Here’s her take on the subgenre:

I would also note that crime fiction experts differentiate between a “locked room mystery,” in which a crime takes place in a fixed location that is literally cut off from the outside world, and “closed circle” mysteries, which involve a limited number of suspects in a fixed location, though the location may not be quite literally “locked”—it might be more of a remote or inaccessible setting, for example, a ski chalet cut off from the rest of the world by a snowstorm. … In modern-day crime fiction, there seems to be a strong trend towards locked room-style mysteries that might more accurately be described as “closed circle” mysteries: stories in which the “locked room” concept is applied to opulent estates, atmospheric islands, or even remote towns. There is obviously a tremendous amount of stylistic similarity between a traditional locked room mystery and a closed circle mystery, and given that, I have to admit that I’m not super concerned with the differentiations between the two.

Okay, I get it! But shouldn’t I read at least one real locked room mystery?

The Life of Crime by Martin Edwards got me thinking this way, and this post counts as another installation in an increasingly spotty attempt to cover Edwards’s entire book. “Locked Rooms” is the 18th chapter.

According to Edwards, locked room mysteries “have the same mesmerising appeal as miracles and magic.” They’re easier to pull off in story than novel form. Example: Poe’s “The Murders in the Rue Morgue,” one of the earliest and best-known locked room short stories.

But tricky as they are, locked room novels took off, especially in America during the Golden Age of detection, the most famous being The Hollow Man by John Dickson Carr2, involving a recurring investigator named Gideon Fell. The plot involves a masked man, a gunshot, a missing weapon, and footsteps that should be detectable in snow, but are not. (It’s hard to summarize LRMs while avoiding spoilers. That was my Wikipedia-aided attempt!)

Hollow Man is famous for breaking the fourth wall and discussing locked room classics and tropes directly with the reader. In the same analytical spirit, Edwards (crediting Robert Adey, who wrote an entire bibliography of locked room solutions) helpfully includes a list on p. 209 of twenty common solutions to locked-room “howdunit” puzzles including, for example: suicide, remote control, animal, “the victim was killed earlier but made to appear alive later,” “presumed dead but not killed until later,” “acrobatic manoeuvre,” “secret passages, sliding panels etc.”

Why didn’t I read The Hollow Man this week? Because so many reviews mention cardboard characters and the available Amazon e-book is evidently missing a chapter! Tell me if you’ve read it!

Edwards’s book outshines most crime fiction articles and listicles not only because he’s more comprehensive but because his scope is more international. He covers Yukito Ayatsuji’s The Decagon House Murders (1987), about seven members of a university mystery club “isolated on a small island with predictably fatal results,” a structure clearly borrowed from Agatha Christie’s And Then There Were None, as Ayatsuji acknowledged.

Perhaps you already know that new Japanese classic. (Not pretending; I didn’t!)

But Edwards goes further, also covering the tradition of French LRMs, mentioning a certain Marcel Lanteaume, who wrote locked room mysteries to “overcome boredom while the prisoner of the Nazis.” He had to await liberation for The Thirteen Bullet, about a serial killer, and two more novels to be published, but his novels—already out of style, according to Edwards—were not a smashing success, and Lanteaume destroyed the rest of his manuscripts written in captivity!

Now that is a historical novel with a mystery inside of it waiting to be written. A Frenchman held by the Nazis, writing ingenious puzzle stories, surviving a “locked room of the heart” (so to speak) via his imagination. Reader, I’m giving you this novel idea for free! Tell me when the movie version is available on Netflix!

I finished reading Edwards still unsatisfied, wanting to know if locked room novels—the real kind, not merely a closed circle classical or cozy mystery form—have simply gone out of style. I found myself wondering if the pandemic, when most of us were stuck inside, was the final nail in the coffin.

Alas, it appears that one COVID-era LRM has been published. Locked Room: A Ruth Galloway Mystery by Emily Griffith uses the pandemic as backdrop for a mystery involving a dead librarian, a string of suspicious suicides, and a mysterious skeleton. From reviews, I was unable to tell if this novel is truly “locked room” or just “lock-down.” I’m leaning toward the latter. Being unsure, I couldn’t put this one on my TBR yet.

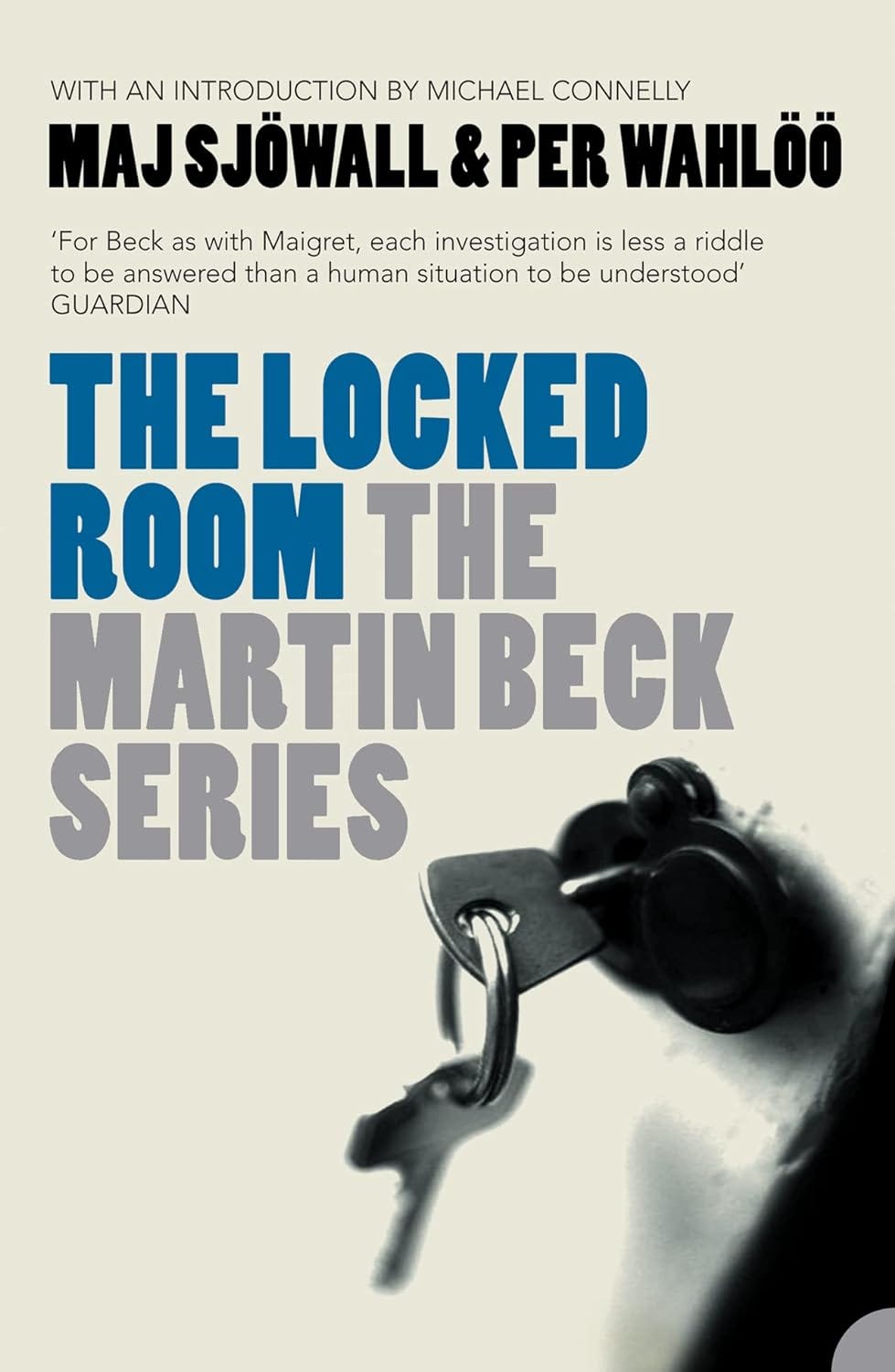

Despite reading Edwards’s chapter, and googling until my eyes hurt, I didn’t find a locked room mystery that appealed to me until locating a Nordic noir classic, The Locked Room by Swedish crime-writing duo Maj Sjowall and Per Wahloo, an installment in a procedural series featuring Martin Beck. The 1972 novel follows the investigation of a bank robbery and, separately, a true locked room mystery.

Unlike classic mysteries involving a brilliant detective and assorted characters immediately captivated by the puzzle of a sinister villain who seems to have done the impossible, The Locked Room by Sjowall and Wahloo begins the opposite way. A much-decayed corpse is found in a Stockholm apartment but police bumble the case from the start, hardly noticing they failed to find a weapon. So how was the victim shot? The case is incorrectly labeled a suicide, a presumption echoed by an inexperienced medical examiner. It’s left to Martin Beck, recently back to his job following a medical leave, to realize the death is, in fact, inexplicable.

Unlike early LRMs that were “supremely artificial” according to Edwards, and plot-focused to a fault, Locked Room by Sjowall and Wahloo opens with gritty realism and round characters. Beck is especially interesting as an investigator trying to escape the pain of a failed marriage and his own recent brush with death.

I’ll be honest. I started the Nordic-noir Locked Room yesterday and I refuse to end this newsletter pretending I’ve finished it, because I haven’t! But I am hooked!

I leave you with this image: on my British Columbia island, the snow blankets the Douglas firs and cedars. Everything is quiet. Even the local ravens and backyard roosters seem to be sleeping. Our two dogs, who hate the cold, are snuggled up on the bed as I write this. It’s the perfect moment for a locked room mystery—specifically, a Scandinavian locked room mystery. And now, no more weeds. Now, I simply read. Ahhhhhhh….

P.S. Please. Tell me if you think the locked room vs. closed circle distinction even matters; if it does, which do you prefer? Share your favorite LRM or CCM titles here, and if you have an opinion about Ware, Foley, and other authors who excel in writing isolated, atmospheric plots, do tell!

I’d argue that the majority of mysteries are closed circle to some extent, certainly the most traditional kind, which is why it’s too big a category and shouldn’t be confused with the narrower-niche locked room mysteries. Am I wrong?

Fun extra, via Edwards. Carr once offered this craft tip: “Write a lie as though it were true… The most important clue should sound like the wildest nonsense; in placing a cryptic clue, be sure that your reader never sees it at eye-level. This can be done using love scenes or comic scenes.”

As a book nerd AND lawyer, I really enjoy overcomplicating what words mean. I also struggle to think of a true LRM I’ve read. (All I can think of are riddles, most of which involve ice as the answer!) I definitely love CCMs.

I think that maybe the distinction matters more if you're *writing* than if you're reading. If you're wanting to write an LRM, then you have to stay in that lane. I read Foley's Guest List and it was perfectly enjoyable. I like the closed circle mode for the reasons Ware mentions: there's less room for that deus ex machina TA DA, which so often wrecks a perfectly good story. Ruth Ware's books are great -- I thought Zero Days was big fun & nicely twisty. The mytery set at Oxford -- The It Girl, I think-- was also really good. An LRM, but in a flashback form.