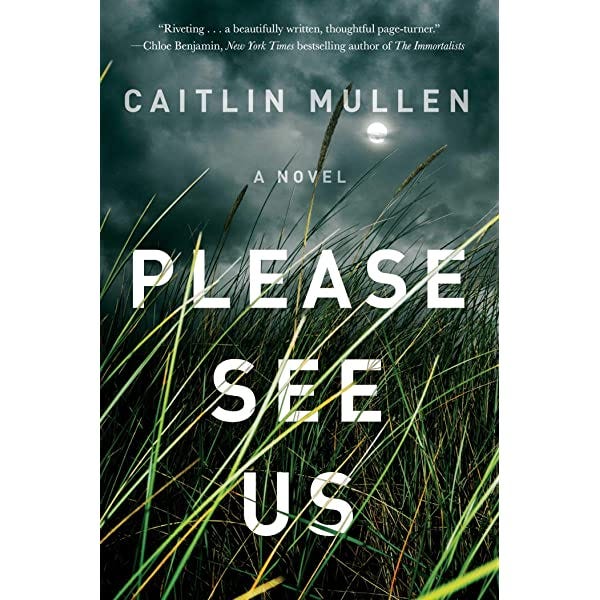

Reverse outlining lessons from an Edgar winner

PLEASE SEE US author Caitlin Mullen shares one of her essential craft tools for developing and revising suspense fiction

At a recent reading I gave someone asked me just how I came to write crime fiction.

I told her the truth: mostly by accident.

I often say to my students that if you had told me in my late 20s, when I was starting graduate school, that I was going to be known as a crime writer, it would have been like telling present-day me that in another five years I will fly a commercial airplane across the Atlantic.

I loved to read crime, but writing crime—a genre conventionally associated with careful pacing, intricate plotting, and the high-wire act of managing suspense—seemed entirely outside my skill set as a writer. I entered graduate school a former poet, sound and sentence-obsessed. I still flush when I think about my first graduate school fiction workshop and the way I was torn to shreds for writing a story that was entirely interiority and backstory. But I left with a crime novel as my thesis, a revised version of which would go on to win the Edgar for Best First Novel.

Maybe the more germane question for an audience interested in writing suspense is, how did I learn to write a crime novel? What tools, philosophies, and revision strategies did I have to learn to transform my work so dramatically?

Before I began PLEASE SEE US, I had been working on a different novel for my graduate school thesis, one full of descriptive passages about the ocean, people with difficult feelings that they never confronted one another about, set in a beach town not unlike the one where I grew up. But there was a story that kept tugging at my attention, something that had happened a decade before and that I couldn’t stop working over in my mind. My novel was inspired by a real-life crime—the discovery of the bodies of four sex workers behind an Atlantic City motel in 2006. I had gone to high school in the area and worked in Atlantic City during the summer. The case remains unsolved. This too, is part of the reason I felt such a compulsion to write about it: I wanted to explore why this story had been forgotten and my own questions about whose stories we listen to and whose we ignore.

I gave myself the summer between my first and second year of graduate school to see how far I could progress on this new idea, which meant I had to swallow my fear about writing a crime novel and turn it into a project that felt manageable for me. Maybe this is true of any novel, but I had to find the skills, the tools, that this particular story needed in order to do it justice. I had to learn what made a suspense novel tick, how my experience as a reader was manipulated so to create that breathless, urgent reading experience that I associated with the crime novels I loved.

In his wonderful book The Science of Storytelling, Will Storr describes how great writers exploit the human inclination to seek information and close gaps in our understanding.

Closing these gaps is a form of control and as humans we crave control as the antidote to danger—because that’s what, in the human mind, the unknown represents. The threat lurking in the dark corner. The stranger we can’t make out in the shadows. The ugly truth we suspect but can’t quite articulate.

It helped me to think of creating suspense as a matter of balance: giving the reader enough information to feel like it is possible for them to have control of the scenario (the plot of the book) but leaving enough room for their questions, formulations, and assumptions to play out in the spaces where they don’t have all the answers. Storr’s book was published after I had finished my work on PLEASE SEE US, but it articulated something that I had learned through the process of teaching myself to write my novel. To make this idea work in service of my book I relied on a tool used by lots of writers, but one that I stand by as essential to creating suspense: a technique called reverse outlining.

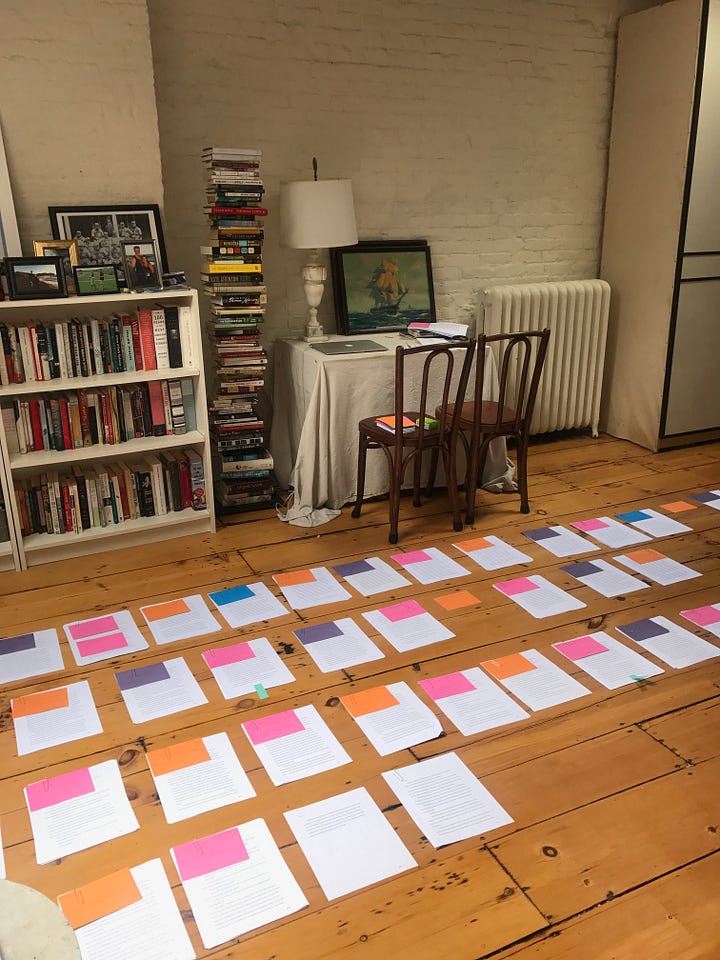

Over the revision process, I used two kinds of reverse outlines for my book in order to help me better manage the pacing and plot. Once I had a first draft I lay the entire novel on the floor, broken out chapter by chapter. Each chapter got its own index card and on top of the card, I wrote three simple pieces of information: What new information does the reader learn in this chapter? What questions is the reader asking? What don’t they know yet?

By questioning this balance of questions and answers, I came up against a lot of problems with the shape and pacing of my book, and it also helped me understand the novel as a matrix of interconnected information, that to pull on one plot thread inevitably changed the pressure on other junctures in the novel. It helped me see what I had done while gesturing toward the possible future versions of the book: the tighter, swifter, and frankly, more interesting versions that it could become.

It is a simple exercise, but one that, at least for me, a writer who doesn’t have a natural inclination toward plotting, helps me keep the reader’s experience forefront in my mind.

Do two chapters merely expand on a problem rather than complicate it? One of them is revised or has to be cut. Is the reader asking the same questions as they were in the last chapter? New information needs to be introduced to keep the story alive and urgent.

I also did this exercise for novels I loved, like Elizabeth Brundage’s ALL THINGS CEASE TO APPEAR and Flynn Berry’s UNDER THE HARROW—an experience that was like a master class in pacing, in deploying and withholding information to maximum effect.

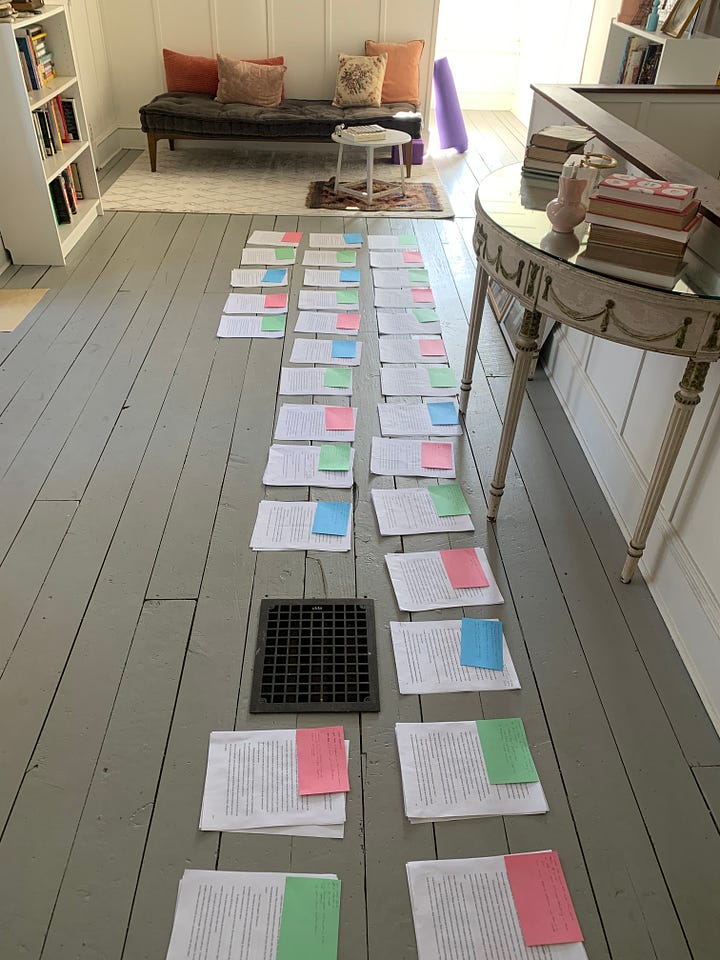

The second type of reverse outlining I do is a little looser and usually happens on a second or third draft, after I’ve smoothed out my plot, moved things around, deleted deleted deleted. At this point, I’ll do a more detailed reverse outline on a big sheet of butcher paper. Working scene by scene this time, I write down what happens, who shows up, what objects appear, what symbols are at work. I note which changes occur and if those changes increase in intensity as time marches forward in the book—if they don’t, then the reader will feel the suspense falter.

If I can, I mine for symbols that can become literal in the plot, that can recur in ways that are useful in urging change—I’ve found that this move can create that sense of intricacy, of convergence, that can feel so rewarding in a suspense novel—in part, because the reader feels active in that synthesizing of information, in control of the clues the novel is offering up.

For example, in PLEASE SEE US, a woman who has fled her unsatisfying family life visits the fortune telling shop of one of my POV characters, Clara. Clara observes a band of pale skin on a woman’s finger, where a wedding band would have gone. In an early draft the image remained in that chapter: a symbol of what Clara couldn’t quite see about this woman’s life, about the people the woman loved and left behind. In the finished book the wedding band shows up later, but this time it functions as a clue to Clara that something ugly may have happened to this woman, adding urgency to her quest to understand where the missing women and girls in Atlantic City have gone—something that she senses is happening in the shadows but that she can’t quite make sense of just yet.

I’m currently facing down the (dreaded!) sophomore novel, and I’m finding it true what people say: that each book teaches you how to write it. But I am also finding it true that the skills and tools that were so hard-won in the process of writing my first book are supports that still serve me in the writing of my second. Even in the messy, often maddening process of getting through early drafts I’m comforted by the thought that so much of what the book needs is already there, and I have come to think that this calibrating work of balancing information and questions is what makes writing suspense—and hopefully, reading it—rewarding and, dare I say, fun.

Caitlin Mullen earned a BA in English and Creative Writing from Colgate University, an MA in English from NYU, and an MFA in fiction from Stony Brook University. She has been the recipient of fellowships and residencies from the Saltonstall Foundation and the Vermont Studio Center. Please See Us is her debut novel.

P.S. Still reading? We loved this interview with Caitlin at Fiction Writers Review. In it, she shares more about her process and discusses the themes in her work.

I used a method that sounded very similar (although never the butcher paper part and the focus on symbols, which is brilliant!); it was from Susan Dennard's website. I LOVE LOVE LOVE that you broke down books you loved using the same method; I feel like that is such a good way to learn. (And delightfully nerdy.)

Oh man, I loved this post so much! I took a Suspense class with Caitlin last fall and it was such a massive help. She's a wise and generous teacher, and I'm so glad this post exists!