At its most basic, suspense might boil down to a single question: what’s going to happen? As a reader, I ask this question more urgently, feel it more in my body, when the characters feel real to me. A lot of my favorite suspense authors write these kinds of characters: Tana French and Dennis Lehane come to mind first. S.A. Cosby’s Razorblade Tears and Liz Moore’s Long Bright River. In these stories, the question became: what’s going to happen to these people?

So what makes a character feel real? I think it’s more than just being flawed or likable. Definitely, there must be something recognizable there, whether it’s me who’s being seen or that I’ve encountered someone like this before. Above all, I react to a character who makes me understand something about myself or someone else. Someone that makes me say “oh, I’m not alone in this,” or, “I guess that’s what it feels like.”

There are probably innumerable ways to write good characters. My favorite lessons in character development are from Francesca Lia Block’s The Thorn Necklace: Healing Through Writing and the Creative Process. Her book is part memoir, part writing guide, and very introspective. Block discusses how a character might have a want and a need: the prior is practical and concrete, the latter psychological and necessary for growth or contentment. The two might be complementary or in conflict, with probably limitless options in execution: a character might pursue want to the detriment of need; she might be driven by a need invisible to herself but apparent to the reader; and so on.

I like teaching these concepts in tandem with one from Lisa Cron’s Story Genius.1 Cron recommends that a protagonist must have a deep-seated, longtime desire, and a defining misbelief about herself or the world that stands in the way of her achieving that desire. This desire and skewed worldview provide rich tension. For example, a character whose deep-seated, longtime desire is to make peace with her sister is interesting, but when her defining misbelief is that her sister is the cause of every bad thing that has ever happened to her? Now we’re cooking.

Personally, I find these four concepts (related but potentially different) to be really powerful to journal about or otherwise put into words for a character. Want and need; desire and misbelief. Fairly simple but endlessly promising.

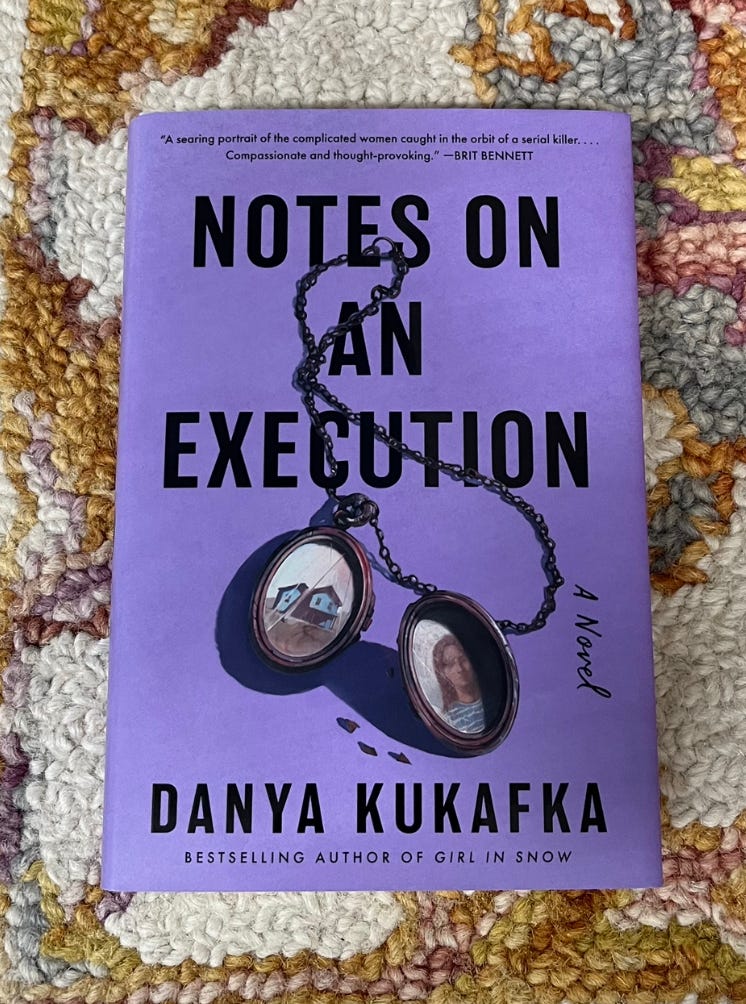

One of my favorite books I read last year was Danya Kukafka’s Notes on an Execution, which mines the lives of four people: Ansel, a man on death row who has killed multiple women; Lavender, who gives birth to Ansel and mothers him in his early years; Hazel, whose twin sister marries Ansel; and Safi, who lives in a foster home with Ansel and, later as an adult, encounters him again. In spite of page one’s proclamation that Ansel is on death row, counting the hours until his execution, the book is suspenseful, each character begging the question: what is going to happen to me?

I don’t know if those first four authors I listed do a lot of work developing their characters during the writing process (though I can’t help but assume they do). But lucky for us, I know Danya Kukafka does, because she sent out a newsletter on the eve of her sophomore novel’s publication back in January of 2022. In it, she discussed the years she spent writing the book, figuring out what it was about, and, importantly, auditioning characters.

Notes on an Execution was born from an earlier novel Kukafka sent off to her agent. After a painful conversation, she found herself essentially scrapping the earlier version–but she didn’t totally walk away. “First, I held a series of auditions. I wrote chapters from the perspectives of a dozen peripheral characters, trying to find the most interesting ones, digging to uncover the real story. I wrote hundreds of pages that I then threw away.” Through this process, three new main characters emerged, “all tiny pieces of that first misguided draft, now pulled forward and pushed to the center.” Those women were Lavender, Hazel, and Safi. Kukafka wrote that she spent “three years working to know them, to understand them, and to finesse their individual worlds.” The result is three women who stand independent of the man who expects to be the center of the novel–the notes are, after all, on his execution. But the women don’t allow him that vanity–by design, Lavender, Hazel, and Safi upstage Ansel in interest and, ultimately, humanity.

In those hundreds of pages of character auditions, did Kukafka think about her women’s wants, needs, desires, or defining misbeliefs? You already know what I’m going to say: I don’t know! But I’m going to use the concepts to analyze a character. Although Kukafka didn’t rely on what I’d call twists for the suspense in her narrative, there are certainly surprises, and so I’ll analyze the character of the four who is the least spoilery, for want of a better word. If you decide to stop reading here, I’ll forgive you, but I’ll never forget.

Ansel’s mother, Lavender, is recognizable to me, in part as a woman and a mom, and in part from my professional experience in child protection law. She is a young mother, abused financially, emotionally, and eventually physically and sexually by her partner, Ansel’s father. They are living in extreme rural poverty. She wants, in a way that I’ve never had to experience, simply to survive. She needs safety and psychic healing. She desires freedom, which is at odds with her misbelief that she is trapped with her husband.2 Some readers might say hers is a tragic arc, where she needed to heal herself in order to protect her son, and she failed; there are many ways one might analyze the mother of a violent man. In Lavender, I think Kukafka sets up an interesting conversation without an easy answer. (Ansel’s violence is Ansel’s fault, but I can’t completely ignore the factors of his upbringing–I lay the blame on his father, not Lavender, and yet I can’t help but reassure myself that I would have mothered him differently.)

This month I’ve been teaching a novel-writing course, which has included plenty of group talk about wants, needs, desires, and misbeliefs.3 I’ve also been coming to terms with some serious problems with my own working novel, which resulted in something of a crisis earlier this week. I had always planned to use Notes on an Execution for my mentor piece on character development, but the timing was divine, because it led me to re-read Kukafka’s newsletter at a moment when I couldn’t have needed it more. Next month I’ll follow up this piece with a recount and reflection on a very recent conversation with my agent, which included her self-described “woo” theories about characters and a line that has made several people laugh out loud at my misery and her cleverness. But in between now and then, I think I’ve got some auditions to hold.

Have you read Thorn Necklace or Story Genius, or otherwise encountered any of the character development concepts in this piece? Do you wish I’d drawn energy graphs again like last time? Go tell it on the mountain! (AKA Please leave a comment, IDK, I didn’t have many jokes in this piece so I’ve gotta get some out of my system.)

The full title is Story Genius: How to Use Brain Science to Go Beyond Outlining and Write a Riveting Novel (Before You Waste Three Years Writing 327 Pages That Go Nowhere) but it was messing with my flow, for obvious reasons…

To call it a “misbelief” may seem callous and inaccurate, because domestic violence does truly trap some, but in this story, Lavender does not remain trapped, which is why I call it a misbelief in terms of her character development and the events that take place in the book.

Great post, Notes on an Execution was one of my recent faves as well

Loved this book so much. My book club discussed it Sunday and we were all just blown away that she made us feel empathy for a serial killer.