Do We Care About How Memory Really Works?

Amnesia, "useful" unreliability, and the return of the Memory Wars

I’m doing edits now on my next novel, which involves psychology, questionable hypnosis, and a few key moments of forgetting. I’m certainly not the first suspense writer to lean into the subject of faulty memory.

Fun fact: Ten silent movies featuring amnesiacs were made prior to 1926! (And many more amnesiac movies followed—the NIH linked paper above proves that scientists have a sense of humor.)

Fun fact #2: Original “Gone Girl” Agatha Christie herself went missing while in the supposed thrall of a dissociative fugue state!

Psychological thrillers often rely on the amnesia trope or its close and more realistic cousins—partial forgetting or memory unreliability due to trauma, head injury, drinking, drugs, grief, or even sleep deprivation.

As consumers or creators of this trope, do we actually care how memory works? Or do we just want to read or watch a fun story about failed memory?

In S.J. Watson’s Before I Go To Sleep—a real treat, especially if the ending hasn’t been spoiled for you by the excellent movie adaptation with Nicole Kidman—a woman has to wake each day with no memory of what happened before, due to a head injury. Her only recourse is a diary that provides clues about her former life.

Can that kind of overnight forgetting, also used in non-thriller storylines like 50 First Dates, actually happen? It hadn’t been documented by researchers, this peer-reviewed paper says, until a bizarre and fascinating recent case that demonstrates fiction’s power to shape our beliefs.

A subject named FL was found to have functional amnesia following a mild brain trauma caused by a car accident. After robust testing that produced complex results, researchers came to believe FL’s pattern of forgetting was influenced by what she’d seen in movies like 50 First Dates. They didn’t believe she was deceiving or malingering—pursuing some benefit of faking amnesia, in other words. They noted that FL seemed to lack full conscious control over her condition. Unknowingly, she was allowing her knowledge of a story to shape how her own memory failed in the face of a stressful condition and very real depression.

I’m fascinated by the FL case, but I’ll be honest. I enjoyed Before I Go To Sleep (and 50 First Dates) without needing to know whether overnight amnesia was a known condition. It seemed possible, and in the world of thrillers, that was enough for me.

Let’s look at a more common form of forgetting.

In the wildly successful Girl on the Train, alcohol provides the key to narrator unreliability. Paula Hawkins told the CBC she was interested in memory loss from the start. “It's a useful device in the thriller, to not remember something you've seen.”

Useful. Exactly. This is how we suspense writers think. We may start with a character or a theme, but at some point we need to get our plot wheels turning, and often, missing information provides a crucial lever.

When you think about it, we really only have two main choices for creating useful “not-knowing” in domestic suspense fiction. Information is withheld by an outside party or it’s kept locked away due to some mechanism of the character’s own mind.

Still, when I first read Girl on the Train, I had a hard time believing alcohol blackouts could be so profound. I was wrong. “En bloc” blackouts and even more common “fragmentary” blackouts (or gray-outs) were reported by 50% of drinkers in this study.

(Hello, Blackout by Erin Flanagan!)

Playing around with a BAC calculator while writing this post, I was re-educated in the difference between women’s and men’s bodies when it comes to alcohol. My husband weighs only twenty more pounds than I do, but according to the calculator, my blood alcohol level was probably twice his after we consumed about the same number of drinks at a recent VP debate watch party. (Even now, I don’t remember who won that debate. Kidding!1)

Paula Hawkins was right to point out that not only are alcohol-related memory lapses common, but a blackout “doesn’t necessarily happen in a uniform or predictable way.” A few drinks in a short amount of time could render many of us unreliable.

You’ve made it this far. Let’s dig into something more controversial.

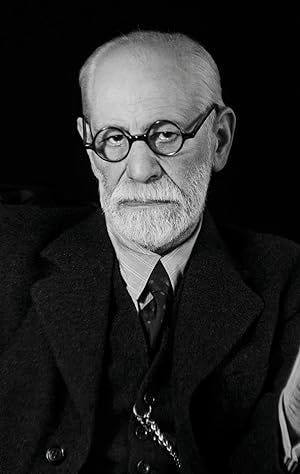

You’ve heard of repressed memories? They don’t exist, suggests Jena Martin, writer and producer of an illuminating and bingeable podcast, The Memory Hole, about the recovered memory movement of the 1980s and the so-called Memory Wars of the 1990s, which include a repudiation of Freudian theory.

The same conclusion is offered in this 2021 scientific paper.

In brief:

“The scientific support for unconscious repressed memories is weak or even nonexistent.”

“A wealth of research demonstrates that traumatic experiences are not repressed but actually well remembered.”

Nonetheless, “the controversial issue of unconscious blockage of psychological trauma or repressed memory remains very much alive in clinical, legal, and academic contexts.”

Both Martin and many memory experts make an intriguing point: in the case of some of the most disturbing events imaginable, people remember too much rather than too little. Studies of Holocaust survivors, Japanese/Indonesian concentration camp survivors, and victims of repeated sexual abuse demonstrate that victims rarely block out those incidents.

The fact that many memories, both positive and negative, are forgotten and can be retrieved using certain cues, or that childhood abuse that wasn’t understood as abuse can be forgotten and reinterpreted in more traumatic terms later, or that people undergoing trauma experience fragmentation, depersonalization, and other defense mechanisms, does not mean these are “repressed memories” in the classical sense.

Problematically, many forms of therapy still used today—often by clinicians unaware there is little scientific evidence for “repression”—can lead to the creation of false memories.234

The so-called Memory Wars of the ‘90s appear to be returning with a vengeance, according to this 2019 paper which reviews the evidence, controversies, and damaging popularity of therapeutic treatments with adverse effects. (If you skim only one paper cited in this blogpost, this is the most comprehensive.)

If over two-thirds of clinical psychologists seem uninformed about the last twenty to thirty years of memory research, which has overturned common ideas from the Freudian 1890s through the Talk Show 1990s, what is my obligation as a suspense author?

I’m willing to dramatize—to stretch the truth beyond known science—especially in the case of a high-concept, clearly outlandish premise like the one in Before I Go To Sleep, even knowing such a story could mislead the rare person into inventing his or her own amnesia.

But ideas about completely repressed memories, as a category, are not rare and “high concept.” They pervade our culture, with very real psychological and legal consequences. Until recently, I didn’t even know to question them. I still have lots to read and learn. In the meanwhile, I, for one, will think twice before I add to such widespread misunderstandings.

P.S. Big thanks to Jena Martin, whose The Memory Hole podcast provided ideas and entertainment just when I was grappling with these ideas and preparing to dive back into my novel revision.

P.P.S. Not coincidentally, I’m teaching a 2-session online 49Writers course Nov 2 and 9, “Memory as Muse,” in which we review a little science and then play with lots of prompts to bring our flawed memories into creative practice.

Please vote, friends.

Still curious? Elizabeth Loftus, memory unreliability researcher behind the controversial “Lost in the Mall” study, discusses the problem of implanted memories with real-life repercussions in this Ted Talk.

Hey, what about that PTSD therapy called EMDR? A skeptical look here, via Scientific American.

Thanks for this fascinating post, Andromeda! Lots of fun sources to explore.

I was curious about the EMDR controversy.

In my experience, EMDR diffuses the charge in troublesome memories. Thanks to hypnosis and the overwriting that happens each time I remember a particular thing (through my "current self" filter), I get a new ending. I've always chosen a happier one!

Still working though, Why We Remember, by Charan Rangananth, packed with information about rewriting, remembering and reconstructing the past. Highly recommend!