Life lessons from Agatha #5. Agatha Christie's working notebooks are a mess—aren’t you glad?

Jotting notes for ourselves is adequate. Case closed.

Would you like to feel inadequate as a diarist, note-taker, or scribbler of any kind? If so, check out Substacker Jillian Hess’s article about Guillermo del Toro’s illustrated diary or “grimoire” (book of magic spells), complete with blood-like ink spatters.

Or, thanks to Hess again, take a peek at director Francis Ford Coppola’s Godfather binder, bulging with brilliant thoughts about his adaptation of Mario Puzo’s book. Coppola was so worried he’d lost the precious binder, which he lugged around everywhere, that he offered a reward, should anyone find it.

Still here? Good! Let’s feel better about ourselves and look at how a disorganized, unartistic, and possibly even illegible journal or notebook can still be helpful to the creative process, as proven to us by one of the most productive and successful novelists of all time.

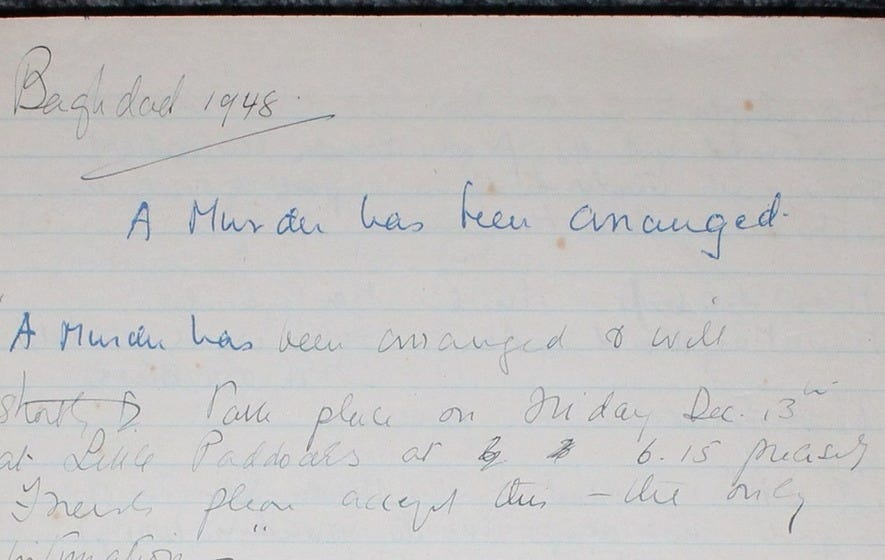

According to John Curran’s Murder in the Making (2012), one of two Curran titles dedicated to Agatha Christie’s 73 working notebooks, the Queen of Crime’s notes are messy, random, and hard to read:

“In only five instances is a Notebook devoted to a single title.”

“At her creative peak, her handwriting is nearly indecipherable.” Interestingly, we often assume that handwriting declines with age, but it seems that Agatha’s mind was so teeming with ideas when she was younger that her hand couldn’t keep up. It’s only as she ages that the writing becomes less unruly.

“Use of the notebooks was utterly random. Christie opened a Notebook…found the next blank page, even one between already filled pages, and began to write. And to compound this unpredictability, in almost all cases she turned the Notebook over and, with admirable economy, wrote from the back also.”

This last point, in particular, eased my sense of fraudulence as a note-taker. I, too, have notebooks that cover multiple projects, and I, too, turn them upside down, writing from both directions. Often I forget I even have a notebook for a certain project, and start jotting somewhere else. (Help!)

I’ve gotten worse, not better, with age as a chronicler of my own ideas and work processes. My journal for my very first novel, The Spanish Bow, includes work calendars, carefully sourced notes, neatly recorded thoughts for myself to ponder about what my characters want, and even sketches from a research trip to Spain. They are legible, functional, and proof of how hard I once tried to stay organized.

My most recent notebooks are a scrawl of revision ideas, writing group comments, scraps of invented dialogue, incomplete timelines, questions for myself about what’s to come next, plus lots of blank or nearly blank pages. I do somewhat better with historical fiction, which relies on research I know I’ll have to revisit. But with suspense, all rules are out the window. Somewhere within these notebooks are ideas and facts I may need, except that I probably won’t find them when I need them. What gives?

I’ve decided in the last few years that the main benefit I derive from a notebook is thinking more than documenting. The mere act of writing things down prompts new questions and ideas. It isn’t meant for others to read—perhaps not even my later self to read.

I’m reassured by Curran’s suggestion about Agatha: “It is debatable whether even [Christie] could read some sections” of her notebooks.

Which isn’t to say the notebooks aren’t packed with detailed plans for some books—as much as 75 to 100 pages in some cases—or that she didn’t re-read her own notes at times to remember an old idea or an entire series of imagined scenes.

Sometimes, Agatha was more orderly. And sometimes she was not.

According to Curran, when asked about her working method in 1955 on a BBC radio program, Agatha said, “The disappointing truth is that I haven’t much method.” But as Curran asserts, “indiscriminate jotting and plotting in the Notebooks is her method. This randomness is how she worked, how she created, how she wrote. She thrived mentally on chaos, it stimulated her more than neat order; rigidity stifled her creative process. She used the Notebooks as a combination of sounding board and literary sketchpad where she devised and developed; selected and rejected; sharpened and polished; revisited and recycled.”

Whatever the notebooks meant to Agatha Christie herself, it’s fascinating to see what they mean to us now, as readers—what they can reveal about one writer’s method, as chaotic (Curran’s word, not mine!) as it might have been.

Agatha Christie was at least partly a pantser:

Curran tells us that “In very few cases is the identity of the murderer settled from the start of the plotting.”

Agatha Christie was also a composter/gardener:

Agatha scribbled down ideas that, in some cases, weren’t used for many years.

Agatha Christie didn’t ruthlessly separate art from life:

Some notebooks contain chemical formulae from her days as a student pharmaceutical dispenser. Some contain French homework. One notebook has a list of furniture, another a list of train times, and yet another a reminder to make a hair appointment.

These details help me envision Agatha Christie wandering from room to room, picking up a notebook here, scrawling a note there, alternating work and studies or chores.

It also reminds me of a confession she made about some of her famous author photos, taken in an office, next to her typewriter. Agatha confessed that visiting journalists always wanted her to pose that way—in her supposed workspace, with the tools of her craft. But the truth was, she wrote everywhere, using everything at hand, even if it was a laundry list with enough margin space to jot some character names.

My months of reading about Agatha Christie’s life, a little project that will soon be taking a pause, have convinced me there are many ways to be productive and creative and many ways to think about oneself as an author. We don’t have to be meticulously organized or deadly serious if we don’t want to be. We don’t have to submit to the idea that every aspect of writing is endlessly hard.

Sometimes, it’s fun. Sometimes, it’s fast. Sometimes, it’s just that thing you do in-between studying chemistry and French, or indulging your taste for sweets, or doing some Middle Eastern archeology with your new lover.

You make it look like the best job in the world, Agatha. Thank you for that.

More for the curious:

“I felt like I died and went to heaven.” John Curran on opening the lidded box that contained Agatha’s 73 notebooks. “I stayed up until all hours the first night I came across them.” Discovering a lost story; learning to decipher Agatha’s handwriting, one of the few people able to do so. A 5-minute YouTube interview.

Ok now I feel better about my current novel’s notebook looking more like a “choose your own adventure”.

I love this one so very much; such a good reminder after so much exposure to beautiful / aesthetically pleasing notebooks through social media (which I look at on purpose, oops). I love her whole work process!