The most famous, bad-ass American mystery writer you never heard of...

Part II of our six-month no-pressure book club, discussing The Life of Crime

In her day, she was more popular than her rival, Agatha Christie. Her first novel, written in financial desperation, sold over 1.25 million copies.

She never used the phrase “the butler did it,” but in one of her books, the butler did do it, and she is credited with popularizing the concept. Even more astounding, in real life, she barely escaped a murderous attempt by her own household cook. (Not a butler, but he was actually mad about not being chosen to be her butler. Life is indeed stranger than fiction.)

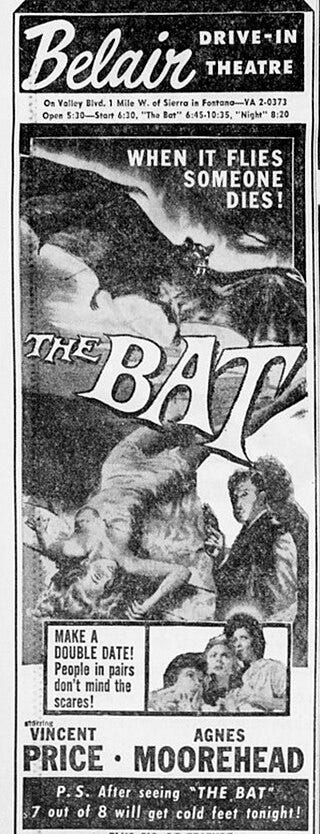

And third—are you ready for this?—she wrote a novel and play about a bat-like criminal who probably helped inspire DC Comic Artist Bob Kane.

If you can name this famous lady, you are a more educated reader than I am. But first, let me intentionally digress to update you on the progress of our little book club here.

Truth is, this party is smallish so far, though I don’t regret establishing this deadline, which forced me to keep up my scheduled reading for the second month in a row. I hope you’ll join me soon!

Maybe my mistake was telling you we’d have no guacamole—or wine. Bring out the guacamole? And the wine! It’s not too late to buy this book and start reading (and yes, skimming or chapter-hopping is just fine).

I can promise you several things. Your TBR will explode. You will discover fascinating human beings and storytelling patterns that have led to the crime fiction world today. If you are a writer, you may also find stories worth updating/imitating/stealing!

Now that I’ve told you some good reasons to read The Life of Crime, let me give you some warnings.

After reading chapters 6-12, I feel inadequate as a writer. I expect this pattern to continue.

The Life of Crime’s 724 pages are bursting with mystery and suspense novelists who wrote at a quick pace, had big readerships, and—let’s be real—made a lot of money. On the productivity front alone, it reminds me of something I’ve noticed in publishing, generally. Writers used to write more than they do today. They were expected to, and allowed to. They seemed less precious about their output. A few were hacks, sure, but many of them were the very opposite of hacks. They took chances. They experimented with structures and ideas. They wrote stories and novels and, often, plays and movie scripts as well. If one book didn’t find favor, no problem—another would be coming soon.

Since the 1980s, we seem to have moved toward a blockbuster mindset that rewards authors who write the occasional book, marketed with maximum fanfare, over the more workman authors who publish regularly.

I can hear you saying, “But only commercial/genre authors publish with extreme regularity!” But that isn’t true. Many esteemed literary novelists used to publish much more frequently than today’s literary darlings.1 (I am hiding the evidence in a footnote because I realize most of you aren’t as obsessed about this as I am, but trust me. There is evidence.)

Once upon a time, writers were expected to find their voices and subjects over time. In other words, to develop.

In The Life of Crime by Martin Edwards, we are witnesses to that development, as entire schools of writers try out different approaches to the writing of mysteries and suspense novels.

Some, like Richard Austin Freeman, beginning in the 1910s, tired of the Whodunit structure and turned instead to the Howdunit, Howcatchem, or “inverted mystery,” in which “the reader knows everything” about the criminal and the crime from the start.

Some satirize crime fiction. A. A. Milne, prior to writing about Winnie the Pooh, wrote a locked-room mystery called The Red House Mystery (1922), a send-up of Sherlock Holmes-style writing that one American critic called one of the three best mysteries of all time.

Some respond to current events—like the horrors of World War I—and bring those events and the trauma of the modern age into what was previously considered “escapist” entertainment. Dorothy L. Sayers explored the damage suffered by battlefield survivors in her mystery novel, The Unpleasantness at the Bellona Club (1928).

And some, like the author I challenged you to name in this newsletter’s opening, did a little bit of everything.

Hello, Mary Roberts Rinehart (1876-1958)!

(Ding ding ding! Cheers to you if you guessed right.)

Rinehart wrote at least 35 novels (and more stories, a bajillion of which were turned into movies or plays), including her most famous bestseller, The Circular Staircase (1908), featuring an unmarried woman who rents a summer house and finds herself contending with a series of strange apparitions and crimes.

The novel was adapted into a play, The Bat, which then spawned several other adaptations—as mentioned earlier, a source of inspiration for Batman. But equally influential was Rinehart’s invention of a trope that would one day be satirized, the “Had-I-But-Known” story, in which a protagonist often laments their poor choices in advance.

I love a good “suck-it-up” story of stoicism and success, and Rinehart stars in a bunch of them. The Pittsburgh-born writer found her way into crime fiction just as Agatha Christie did—out of financial need. In Rinehart’s case, the 1903 stock market crash spurred her to try writing as a way to make income to support herself and her physician husband.

Trained as a nurse, and the mother of three sons, Rinehart also went on to become a war correspondent on the Belgian frontlines of World War I; this lady had some serious political opinions (and influence).

After her husband died, she joined with her sons to start a publishing company, Farrar and Rinehart, one of the most successful houses of the day. Her own backlist got the house off to a solid start. (Farrar later left to create the firm that would become Farrar, Straus & Giroux.)

When Rinehart got breast cancer, she wrote about her mastectomy candidly in a magazine article—something unheard of at the time.

Mysteries! Motherhood! Battlefields! Publishing! Cancer!

The least we could do is read one of this woman’s novels. I, for one, am putting her on my TBR.

Coming up next month from The Life of Crime (chapters 13-18): Early spy fiction! Locked room mysteries! Queens of crime! More reasons for Andromeda to lament her lack of productivity! Join us!

I looked up five authors who influenced me as a young writer.

Here’s the old guard—literary writers who made their names in the 1960s and ‘70s. In the first 30 years of their careers:

Ian McEwan (U.K.), published one book on average every three years.

Philip Roth (U.S.), published one book on average every two years.

Paul Theroux (an American, but lived in the U.K. at the start of his career), published one book every 1.5 years.

Now let’s look at literary writers who got lots of buzz a decade or two later.

Jeffrey Eugenides, three novels, one short story collection. One book every 7.5 years.

Junot Diaz, one novel and two short story collections. One book every 10 years

Am I the only one who sees this as a problem? Compare your favorite authors from the 1900s-1970s versus 1980s-2020s, or in the US versus UK, or both! What patterns do you see? Do you think publishing less frequently is a boon or a bane for the writer’s learning process and mental health?

I was going to guess Dorothy Sayers only because I just read up on her for the greatest mystery and thrillers of all time list! Now gotta add another writer to the list... 😃

I DID know about her! I discovered her last year as she had a connection to my home state of Maine. I also published a blog post about her because I was so thrilled to learn about her and her writing career.