Narrow and Intensify Conflicts to Save Your Story

One draft failed. The other sold. What I learned while revising WHAT BOYS LEARN.

First, a special offer until Dec 14, directly from me! Support indie and local bookstores and receive a free extra book and some special surprises directly from me. But please act quickly. I want to get those gifts in the mail!

Next. Are you curious about treating yourself to an intimate writing and publishing conference aboard an elegant London-to-New York oceanliner, the QM2? I’m answering questions at an online open house tomorrow, Saturday. (Recording available.) Sign up here.

Let’s Talk About How A Failed Draft Became a Sold Book

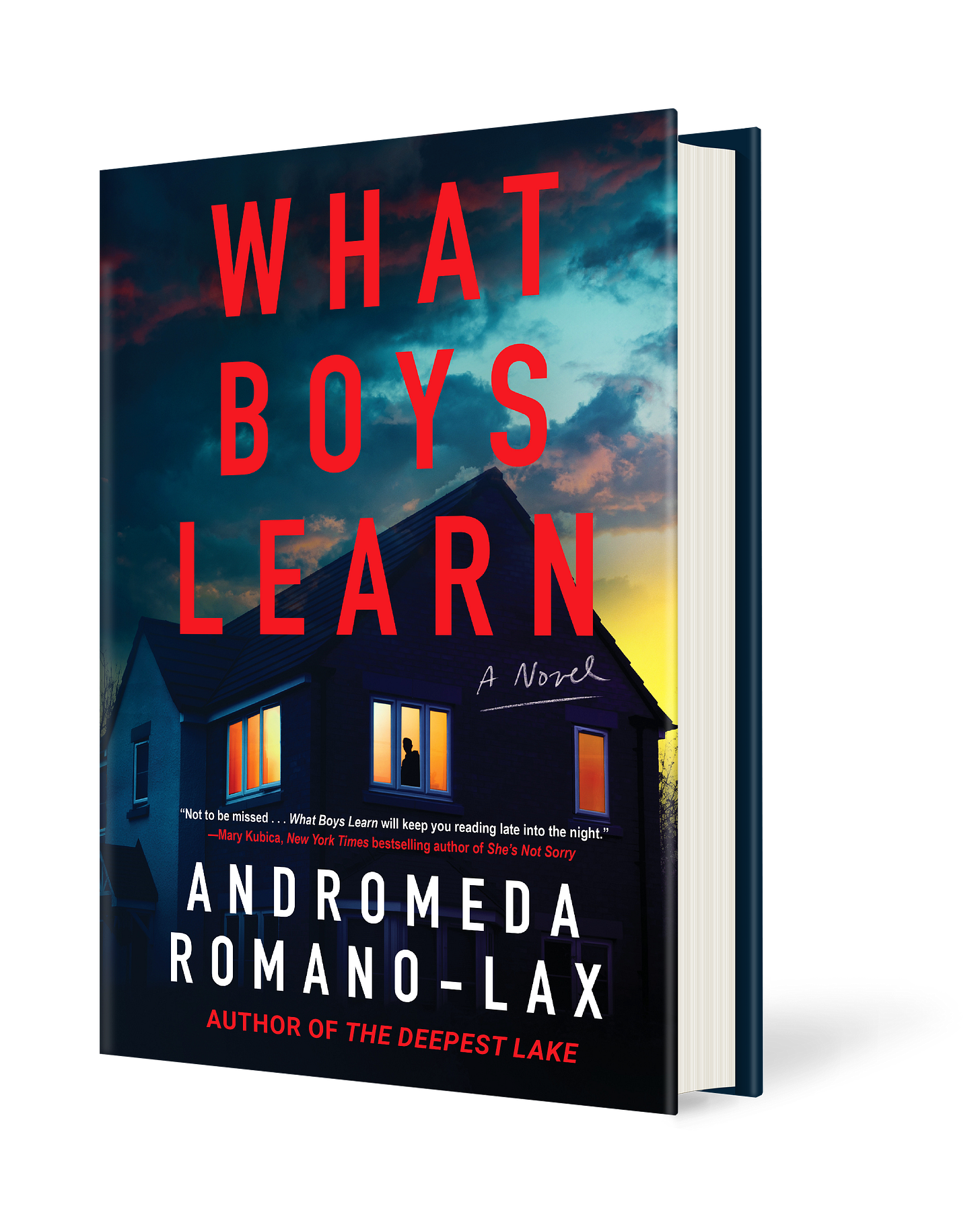

Part of this post ran in 2024 under the title “Keep Your Monsters Close,” but I’ve also edited and updated it now that my seventh novel, WHAT BOYS LEARN, not only sold but is coming out soon, to excellent reviews. (Phewwwww.)

Here’s a story.

A teenage boy who may have committed murder runs away.

Versus this.

A teenage boy who may have committed murder stays home. Denies. Obstructs. Hides things. Seems suspiciously unbothered. Talks too much (to the police). Talks too little (to his mother, who is one step away from a complete meltdown).

Which is the better story?

I tried writing the first version about three years ago. The set-up was fun, especially creating the world of adults—parents and neighbors, all of them misbehaving in ways that would ultimately be connected to the intentionally confusing crime.

As far as the reader could discern from early chapters, the boy may have been guilty or innocent.

In either case, at the first sign of trouble, I sent the boy running away, with his girlfriend. (Cue the opening of Googlemaps, as I charted his escape route and followed the young couple mile by mile, away from their families.)

And that’s where I started getting bored, at around 100 pages, or approximately 25,000 words, for reasons I wouldn’t understand for many months. At 65,000 words—so near to the end, argh!—I set aside the manuscript.

But a year later, after putting the manuscript in a virtual drawer and turning my attention to a different novel, I understood my mistake. I had created a monster, or a possible monster, if the boy had done something wrong. And I had created a house. The house in which he lived. And the bigger “house”—the town in which he lived.

But then I had sent the monster far away from the house. And town. And everything else that grounded him in the story, criminally, physically, and socially.

By sending my antagonist away too soon, I let the pressure out of the system. I didn’t think I was doing it at the time, of course. After all, the boy could be caught! And his mom and everyone else had plenty to deal with and puzzle over, even in his absence. But let me tell you, I sure got bored writing scenes in his POV, as he traveled and evaded communications.

Later, with sufficient distance from the project, I had an opportunity to dig down and think about the scenario from the perspective of my main character, the boy’s mother, Abby. I also had more time to consult my own motherly intuitions. I realized that the worst possible thing isn’t knowing that your child may have committed a crime. The worst possible thing is having a child possibly commit a crime and then still be in your house, in your care, leaving his socks everywhere and taking too many showers and asking for more pizza as you struggle to determine his guilt or innocence and decide on an hourly basis what to do next. How do you protect him? How do you help him? How do you keep loving him?

This is one thing I absolutely love about gaining competence and confidence over time, the more manuscripts one has written. When something doesn’t work, you can choose not to think catastrophic thoughts—this whole thing is a failure, what a waste of time—and instead think, This manuscript needs to be put away. If it’s meant to be, I’ll come back to it with fresh ideas.

It’s happened several times for me lately. Six or twelve months pass. And then, boom, I know exactly what I did wrong and exactly how I can make it right. It’s such a thrilling feeling!

So far, with each temporarily “failed” manuscript, I’ve learned a different lesson.

For the purpose of this post, let’s stick with the problem of a wandering or distant antagonist.

“Monster in the house” is a horror trope, and it usually involves an evil, supernatural entity, a contained environment (whether house or town). According to the trope experts, there’s usually a sin involved as well—something that kicked off the haunting or violence.

I’m only a newbie when it comes to writing horror, but I think this trope has crossover relevance to the suspense genre, especially in relation to the second element, which is containment.

Especially in domestic suspense as versus horror, the containment may be physical—an actual house or closed location— but it can also be emotional— relationships that aren’t easy to untangle from.

Completely by chance, the last two novels I read used a combination of physical and emotional containment to good advantage.

In Ruth Rendell’s Dark Corners, a creepy man named Dermot rents a room from our main character, Carl, and not only encroaches on our protag’s privacy but begins to blackmail him.

In Erin Flanagan’s, Come with Me, a frenemy named Nicola helps out our protag Gwen by getting her a job, and a duplex close to her own, so that they can be together nearly every minute of the day. The frenemy also befriends our protag’s young daughter, infiltrating Gwen’s family life.

A clearly defined antagonist or limited circle of possible antagonists forces our protagonist to make choices and act, constantly. If the author has done a good job, each one of those imperfect choices creates further trouble. (Don’t give your characters too many breaks! Their job is to suffer!)

Interactions between protags and antags—awkward or puzzling exchanges, threatening or weird dialogues—are fun to read and fun to write, all the more so when our main character isn’t completely sure if the villain is truly the villain, or knows but is limited from acting by some circumstance, whether bribery, loyalty, self-doubt, complicity, or something else.

In the case of a definite antagonist, we should squirm as our main character’s dilemma gets even more thorny and inescapable. In the case of an uncertain antagonist, or multiple possible antagonists, we should feel even more dread as uncertainty balloons.

Think of your favorite novels or recent suspense reads. Often, the villain—or potential villain—is a wife, husband, child, friend, frenemy, roommate, or co-worker. The closer the relationship, in some ways, the greater the pressure.

(Let me repeat the title of this post, in case you’re thinking about your own story now: Narrow and Intensify Conflicts!)

The challenge for many of us, when we want to keep the monster (villain/antagonist) close but unidentified and possibly hidden among a limited number of potential antagonists, is how to surprise the reader. After all, in the most contained stories, there aren’t too many possibilities! It’s a challenge, but it’s really worth the work.

But since I’m updating, let me mention a recent TV show that hews more closely to the advice I’m giving you here.

TASK, featuring Mark Ruffalo and written by the same writer who gave us MARE OF EASTTOWN is one of the smartest and most poignant crime series I have seen in a long time. It’s a brilliant show in terms of character arcs. And boy, is it gripping and sometimes claustrophobic. A Task Force team investigates a series of robberies committed by a man whose brother was murdered by a local gang—but that’s only the start. Murder and mayhem ensue, as do very realistic and humane subplots involving family members doing their very best to care for each other. (I cried and cried at the end of one episode.) The criminals are every bit as sympathetic as the “good guys.” On top of that, the good guys aren’t always so good.

In this show, we keep seeing the same people interact with (and threaten) each other because, damn it, they are neighbors and friends. In the world of this story, it is not easy to flee, whether it’s from an abusive boyfriend or a brother with bad judgment or a local gang member sadist. I’m not giving away the plot by telling you to keep an eye on where the biggest threats—both physical and emotional—come from. Not outside, but inside.

In other words, the monsters are being kept close. The conflicts are intense. The geographical scope (and duration, too) are limited.

Decrease volume, increase pressure.

It works.

A final note on variations. Even though I let the last third of What Boys Learn sprawl a little—my characters go on a road trip for a few chapters, from Chicago’s North Shore suburbs, up to Wisconsin—I compensate in other ways, keeping the antagonist and the people who are being threatened most directly even closer, physically. In the novel’s final scenes, there is only one way to escape, and it’s nearly as dangerous as staying put.

Does the ending work?

In a starred review, Booklist had this to say: “Nothing can prepare readers for the running-against-the-clock action of the last few chapters, which, in retrospect, Romano-Lax has set up beautifully. A stunner.”

I hope you’ll consider pre-ordering my book at your favorite local bookstore, Bookshop.org, or Barnes & Noble, or requesting it at your library.

And I hope you’ll have the fun of coming up with new solutions for stories you’ve put away in a drawer.

Do you have any thoughts about how intensifying conflict—whether by shrinking duration or geography, or finding some other way to maximize pressure— saved one of your stories or novels? Share in the comments!

P.S. This is a collaborative Substack. Do you know I have my own free author newsletter as well, with very different content, including deep dives into the author’s life and posts on my various books, including ones outside of the suspense genre? Please subscribe.

This is such a great post, Andromeda! Thank you for this. So much to think about. And I know you know this, but I'm SO EXCITED to read this book!

Great advice I've heard before and needs repeating. Got to turn up the heat on the protagonist: chase him up a tree, then throw rocks at him, then set the tree on fire. Without trouble, there is no story.

I try to throw nothing away, and your example with this manuscript is a great lesson. I treat abandoned manuscripts like a salvage yard, where I can go back and harvest parts, or sometimes resurrect an old idea in a new form.