Louisa May Alcott's dark side, Conan Doyle's thirst for justice...

Rabbits, writers, and readers get started! Life of Crime book discussion, chapters 1-6, with talk of Wilkie Collins, Poe, Braddon, and a bunch of other names that will swell your TBR

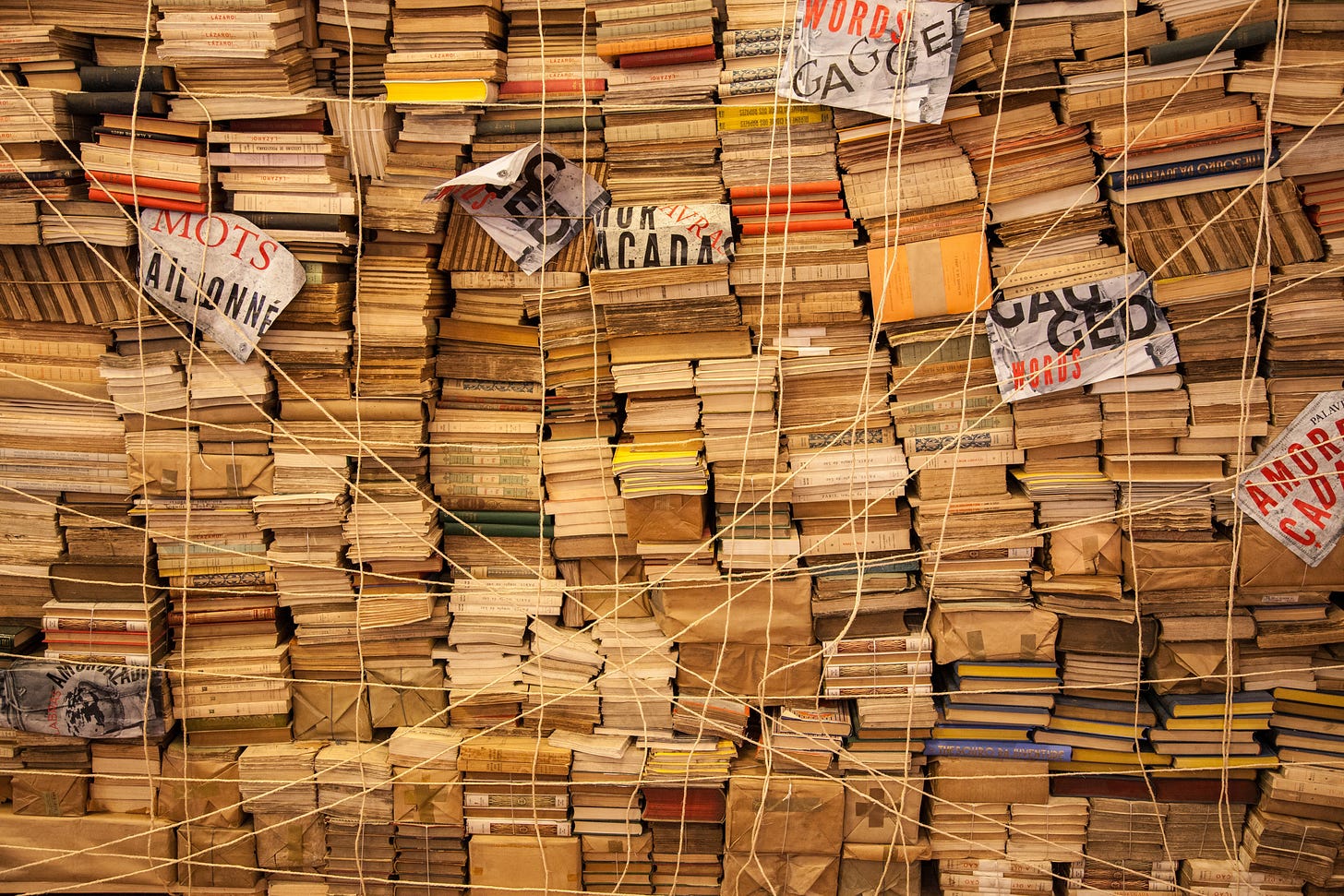

This book is dangerous, I warn you. I stand before you today with bits of soil clinging to my hair and scratches on my arms and legs. No, I wasn’t burying bodies or digging them up either. I was crawling through internet rabbit holes thanks to Martin Edwards’s Life of Crime, the topic of our “no pressure” asynchronous book club.

Ever wanted to know absolutely everything about the history of crime writing? This is your chance. We’ll be discussing the book monthly, in six-chapter increments, for many months, because this sucker is a doorstop! If nothing else, Life of Crime will swell your TBR with influential books to read and titles you feel bashful for not having read years ago.

EARLY TAKEAWAYS

Let’s get one “first” out of the way.

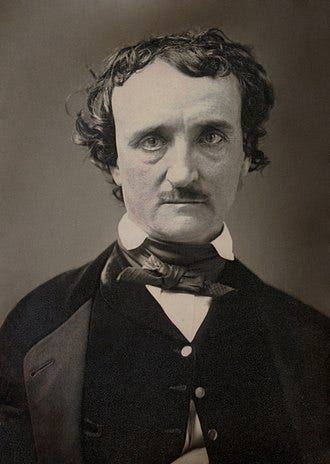

Amaze your friends and improve your crossword savvy. First detective story? Possibly Edgar Allen Poe’s The Murders in the Rue Morgue (1841), starring a detective named Dupin who uses deduction to solve a locked-room mystery involving a body—are you ready for this, Caitlin?—stuffed up a chimney. Note the curious parallel to Tana French’s use of a body stuffed into a tree! Proving that people will do anything to avoid hours of shoveling.

Poe’s Detective Dupin returned in another story about a murdered woman—this one dumped in the Seine, inspired by a real murder of a “cigar girl” in New York. Here, we see another first that will become a theme—writers using real cases as inspiration, and sometimes even trying to solve them. Arthur Conan Doyle and Erle Stanley Gardner also became involved, later, in high-profile investigations.

Despite the claim for Poe’s short story as the “first detective story,” an 1819 “impossible crime” novella by E.T.A. Hoffmann may have beat it. Edwards gives us other possibilities from Germany and Scandinavia (p.16).

By the way, Poe himself died suspiciously, and he may even have been a victim of violent thugs engaging in “cooping, a crude form of electoral fraud.” Poe was en route to his beloved when he went missing and then showed up days later in a delirium, wearing someone else’s clothes and shouting the name “Reynolds!”

A) Why do crime writers frequently go missing (see, Agatha Christie), and

B) Can we see Poe’s last wild days in a movie, or was that movie already made and I missed it?

Everyone you’ve ever heard of has written a mystery or thriller.

Okay, not everyone. But since the late 1700s at least, nary an author seems to have ignored this domain. Ever heard of Mary Wollstonecraft’s father, William Godwin? He wrote the first “pursuit thriller” in 1794, The Adventures of Caleb Williams, about a young man who learns too much about his employer’s nefarious deeds to cover up a murder, and has to flee (p.11). Edwards notes the novel’s publication coincided with the British government’s suspension of habeas corpus, allowing arrest or imprisonment on “suspicion” without charges or trial.

In other words, one of our earliest suspense novels was written to make social or political commentary. We will see that pattern repeated. We’ll also see the fine line between lightly incorporating some questions about society versus writing pedantic novels “with a purpose,” a.k.a. trying to “weaponize fiction.” Edwards claims that another writer, Wilkie Collins (we’ll get to Wilkie soon), lost the thriller knack when he got too preachy in his later books (p.43).

Of those who tried, many of the pioneers popular in their day have been forgotten.

If you’re a writer, this fact prompts major existential angst. Let’s hold hands and breathe.

Women have been major players in crime writing since the beginning.

Sure, we’ve all heard of Agatha Christie and Patricia Highsmith, but what about bestselling sensation novelist Mary Elizabeth Braddon? Her best-known novel is Lady Audley’s Secret, about the problem of accidental bigamy, which was evidently something that gave 1860s folk much anxiety. (Imagine not being able to Google that dashing stranger who just asked for your hand!) About the Victorian-era author, Thackeray said, “If I could plot like Miss Braddon, I should be the greatest novelist ever lived.”

Edwards also devotes paragraphs to Elizabeth Cleghorn Gaskell (who wrote Mary Barton, based on a real murder and included an early mention of forensic ballistics), Caroline Clive, and Louisa May Alcott.

THE FIRST RABBIT HOLE!

The author of Little Women wrote thrillers? How did I not know this? Edwards gives the American icon one scant paragraph. Pause as we stick a bookmark into Life of Crime.

About Little Woman, which she churned out in two and a half months, Alcott wrote in her diary, “Mr. N. [her publisher] wants a girl’s story, and I begin ‘Little Women.’ Marmee, Anna, and May all approve my plan. So I plod away, though I don’t enjoy this sort of thing.”

In an admirably thorough CrimeReads piece, Stephanie Sylverne shares synopses of many Alcott thrillers, some not discovered by scholars until fairly recently. She suggests that suspense was Alcott’s true passion, even if she felt compelled to publish under a male pseudonym.

“I think my natural ambition is for the lurid style … I indulge in gorgeous fancies and wish that I dared inscribe them upon my pages and set them before the public. How should I dare interfere with the proper grayness of Old Concord? The dear old town has never known a startling hue since the redcoats were there.”

Writing Gothic tales of vice, Alcott could indulge her darker side, writing about heroines who “are forceful, independent, sexually demanding, smoke dope and don't do housework,” according to a ‘70s article in the New York Times.

MUST-READ OLYMPICS

Returning to Life of Crime now, let’s fully meet Wilkie Collins, author of The Lady in White and The Moonstone.

Yes, I’d heard of Wilkie before, and I even tried to talk my local book club into reading Lady in White. They said no thanks! (One of them even referred to Wilkie as a “her,” which goes to show that no amount of fame will render you unforgettable to future generations.)

Here’s why I—and maybe you—should read him.

Edwards calls Wilkie “the most influential British crime novelist of the nineteenth century,” and Woman in White (1860; serialized earlier) gives us a plot we’ll see time and time again: a woman is confined to a lunatic asylum as a way to confer advantages on a gaslighting villain. Turns out, this scenario was not at all rare in the real-life mid-1800s, and it didn’t take a long stay in an asylum to make even a healthy person go mad. Fun fact: it was much harder to get out of a private asylum than a public one.

According to Edwards, Wilkie Collins was also a master of realistic setting, establishing atmosphere in a way that impressed Henry James, and he made use of a structure that was innovative for the time, using five contrasting points-of-view in The Moonstone. Collins had already experimented with multiple POV in Woman and White as well, explaining in that book’s prologue that he got the idea from how stories unfold in trial, as recounted by multiple witnesses. (You’re a smart one, Wilkie.)

Wilkie Collins was pals with Charles Dickens, who also wrote crime fiction. Bleak House featured the first “major fictional police detective,” Inspector Bucket. (Note to structure lovers: evidently, in Bleak House, Dickens also played in novel ways with combinations of past and present tense chapters.)

Speaking of Bucket, why do we love detectives so much? Because their investigations “function as thrilling metaphors for the processes by which we all acquire our knowledge of the world” (p. 43, quoting Jonathon Coe).

One last thing about Collins, who evidently was born with a protuberant forehead. He went on tour with Dickens. But the tour was really a cover for Dickens's affair with a woman. That story is fully told not in Edwards’s book, but in a creepy novel by Dan Simmonds called Drood, which conjectures about Dickens’s mysterious final years when he failed to finish a novel called The Mystery of Edwin Drood. Thanks to my own hubby Brian, a lurker who reads every one of these newsletters, yet never comments. Brian tried telling me about this inventive novel, which sounds amazing, years ago. A-hem.

Help, I can’t read all of these books!

My wordcount runneth over, but trust me when I say that even if you are bored by Sherlock Holmes, you will gain much respect for Arthur Conan Doyle and his dark, cocaine-injecting detective by reading chapter six. Conan Doyle didn’t succeed right out of the gate, by the way. According to Edwards, Arthur Conan Doyle spoiled an early book, A Study in Scarlet, with an overly long flashback (the book was rejected by several publishers before publication in 1887; it didn’t attract many readers).

In addition to improving his craft, Conan Doyle went on to incorporate innovative forensics and an emphasis on evidence over intuition into his Sherlock Holmes stories, to the extent that for years, Chinese and Egyptian police used his stories as instruction manuals!

But here comes my second rabbit hole, and it has to do with the writer’s life, rather than his stories. I already knew that Conan Doyle became involved with a campaign to secure justice for a Parsee man named George Edalji, who was convicted of mutilating a pony. (Weird story. Julian Barnes used it in a novel—this one I’ve read already, hurrah!—called Arthur and George).

But did you know that Conan Doyle got involved in proving the innocence of a Jewish man from Scotland named Oscar Slater, who was unjustly accused of murdering a spinster with a hammer? Edwards gives it a paragraph. I went online and lost an hour.

NOW IT’S YOUR TURN!

What historical developments in crime fiction surprised you?

What books are you determined to read?

What was your favorite chapter?

And Caitlin, have you finally found your copy? I recommend looking under the bed.

Oh I love that detail about Louisa and Utopian communities. I’m finding myself suddenly VERY interested in her. Can you please tell me which Wilkie we should read, if we only read one? Is one more interesting in terms of craft or trope-a-mania (I.e., a-ha, that’s where all those suspense tropes came from!)

That NYT quote sold me on LMA’s suspense. That’s my key TBR takeaway