How Limitations Spark Creativity

Plus an accidental Hollywood discovery about suspense: show us less and we will fear much, much more. Guest post by Jamey Bradbury!

Thanks to Jamey Bradbury for this guest post, which is giving my suspense-obsessed brain lots to mull over this week!

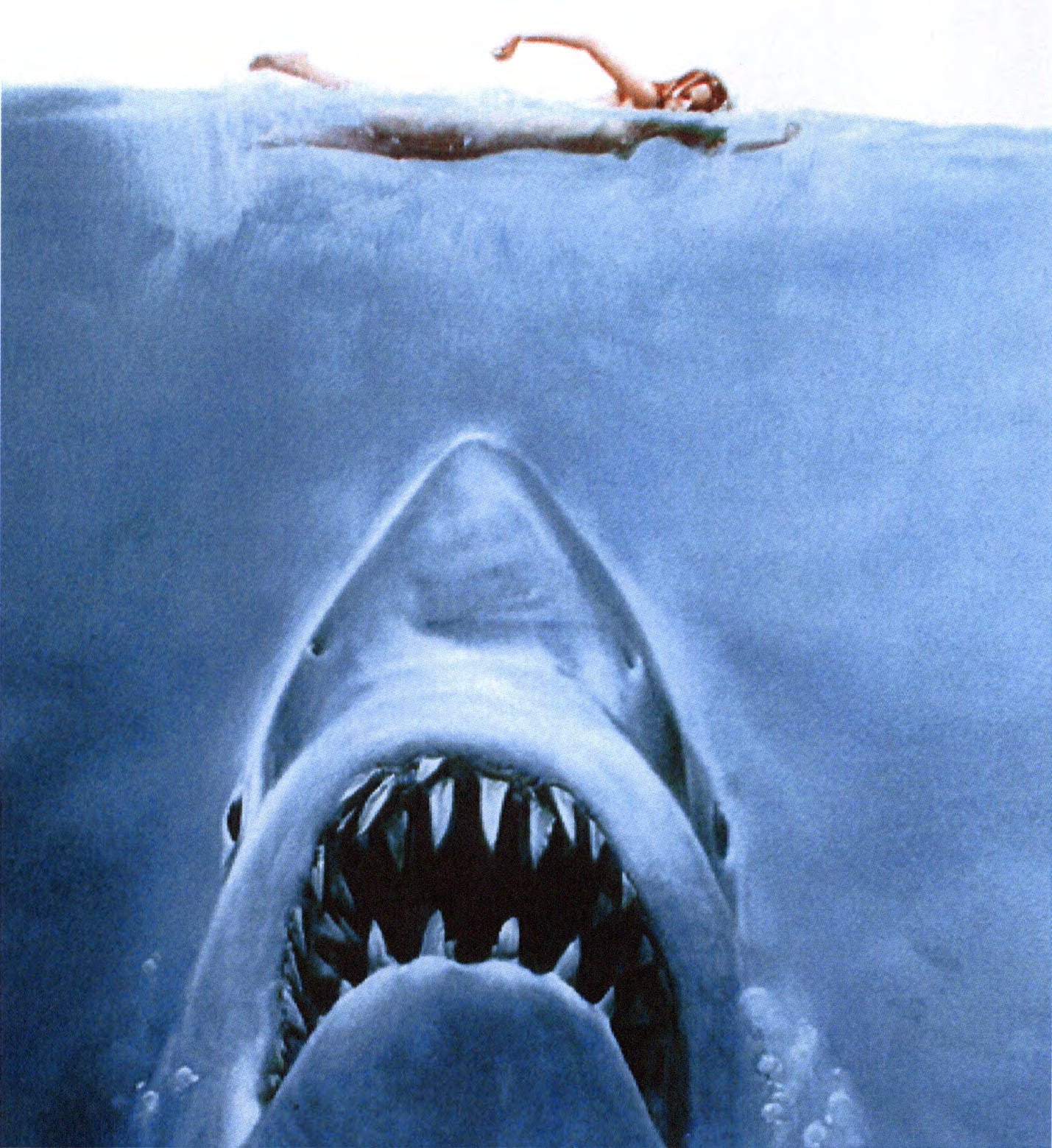

My favorite behind-the-scenes film story comes from Jaws. In 1974, Universal Studios put its man-eating shark movie in the hands of a young and untested director. Jaws quickly went over budget, filming overran its schedule by a hundred days, half the movie’s special effects didn’t work—and yet it went on to create a whole new film genre: the summer blockbuster.

If you’re familiar with the story behind Jaws, you might know that director Stephen Spielberg initially intended to show a lot more of the monster shark than we actually get in the final cut. Problem was, the mechanical shark built for filming (which the crew named “Bruce”) kept breaking down. Of all the actors on the set, Bruce was the biggest pain in the butt. He malfunctioned at the worst possible moments; when he was submerged in seawater, the salt corroded his mechanical guts.

Young Spielberg didn’t have the budget to build a newer, better Bruce. Instead, he rewrote scenes so that the audience would never see the shark until the crucial moment. He relied on sound instead of visuals and let the ominous and now famous score composed by John Williams do the work of building momentum and suspense. Most iconically, he turned his camera into a shark, using it to simulate the shark’s point of view and to mimic movement through the water. What resulted is a movie so famous for its suspense sequences, film students still study Spielberg’s innovative camera use today.

Faced with the limitations of a lean budget and a broken animatronic shark, Spielberg was forced to get creative. That’s what limitations do: they create situations that compel artists to think in new, innovative, or unexpected ways.

If you’re a genre writer, you already know this. Genre fiction comes with a set of rules, and even if you’re the sort of writer who enjoys subverting those rules, you’re still playing with a set of given limitations. Genre writing not only comes with its own rules; it often requires you to create additional rules or limitations to make the world you create more believable.

Setting rules or creating limitations isn’t just about believability, either. It’s also a great way to create tension, suspense, or obstacles for your protagonist. As writers, it’s our job to make things hard on our characters: A romance novel in which the your heroine falls in love with a handsome dude, charms him instantly, consummates the relationship successfully, gets married, and lives happily ever-after isn’t a very satisfying read.

We read because we want to see characters in difficult, challenging, impossible, complicated situations—and then we want to see how these smart, resourceful, ingenious, or just plain lucky characters figure their way out of it.

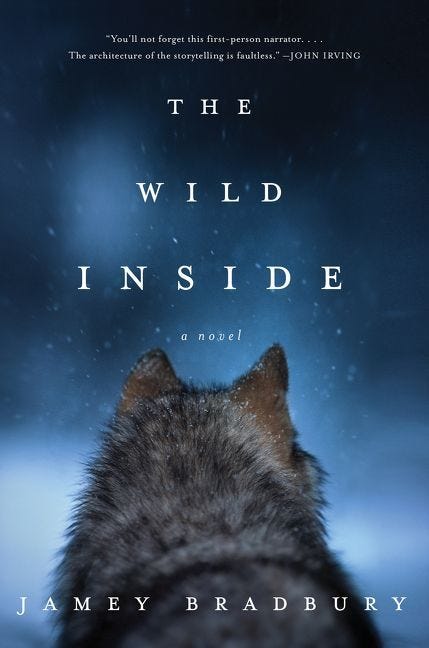

When I was working on my novel, The Wild Inside, I stumbled onto a realization: my character wasn’t the only one who needed to bounce off of obstacles and struggle with her circumstances. I needed to, as well.

The Wild Inside began with an image I saw in my head: a cabin in the middle of a clearing in a snowy forest. I knew there were two people inside that cabin, waiting for a third. Who was this third? What had happened to her? Why wasn’t she home? These were the questions that compelled me to write.

But early drafts of the story quickly fizzled out. I tried writing from a different point of view, from multiple points of view, from a point in time looking back. Third person, first person, journal entries, letters between characters—I tried everything, and nothing seemed to work.

Part of the problem was the blank page. I looked at that vast, boundless landscape and realized: Anything could happen. The blank page can be a place full of the excitement of possibility—but that sense of anything can happen can also overwhelm. How do you decide which “anything” should happen?

Orson Welles once said, “The enemy of art is the absence of limitations.” To put it another way: How can you think outside the box if there’s no box to begin with?

I found a box for The Wild Inside when I read a book called Some of Your Blood by Theodore Sturgeon. The novel’s protagonist, George, grows up in Kentucky. He likes to hunt and trap, and when he gets arrested for assaulting a senior officer and is sent to a military psychiatrist, it becomes clear that George doesn’t just eat the animals he kills; he drinks their blood.

When I read Some of Your Blood, I could only think: What if the protagonist were a woman, instead of a man?

I didn’t know it then, but this question would lead me to make decisions—to set limitations—that would not only heighten the stakes for my characters, but create the voice of the novel.

I had already decided that I would set my book in rural Alaska. Now I decided that, like George, my protagonist, Tracy, would also be a hunter, an explorer of the woods around her home, and a person with a special relationship to animals—both the dogs she works with as an aspiring musher, and the animals she hunts to help feed herself and her family.

The setting of my novel offered natural obstacles and limitations. Here’s some free advice: I highly recommend setting your murder mystery, thriller, or horror novel in a wintry place. Cold climates offer complications that easily build on the conventions of a given genre to create suspense.

In my book, the central tension is whether Tracy will stay home and protect her family from a mysterious threat, or disappear into the wilderness where she feels she belongs. When it came to writing scenes, I heightened the tension between both of those ideas by relying on what Alaska, as a setting, supplied me. As Tracy contends with the wilderness or confronts a stranger in the woods, she also falls through the ice of a frozen lake and nearly drowns. She finds that all her traps are empty and the animals she normally hunts are hiding in their dens; the food she would typically forage is buried under feet of snow. The isolation of her family’s house, the threat of wildlife, the way the weather of an Alaskan winter can suddenly turn deadly—all of this served to make Tracy’s life hell, which served to heighten the stakes and create suspense.

Modeling my book after Sturgeon’s example, I also decided that, as a young woman who’s more comfortable with nature than with people, Tracy would have a very limited understanding of the world beyond her family’s home. I set myself a series of guidelines, or rules, for how Tracy interpreted her surroundings and how she spoke. Some rules were grammatical (using “I could of” instead of “I could have,” or always keeping certain verbs, like “run” and “come,” present-tense), while others were based on Tracy’s understanding of nature. Tracy is a very well read character, but she’s also somewhat naïve, especially when it comes to other people, and these things influenced the voice I developed for the narration of the book, as well. Once I could hear Tracy’s voice and had the framework for how she interpreted her world, I finally found a vehicle that would drive me through the story.

If I hadn’t placed these limitations—of voice, of setting—on myself as a writer, I never would have finally found the thing that propelled me through the draft that would eventually become my novel. It was only when I discovered a way to limit my own writing—a box in which to contain that image I started with—that I found the story I wanted to tell, and the way I wanted to tell it.

Box yourself in. Give yourself something to push back against. Set rules for your story, and see how working within the confines of those limitations forces you to get creative.

You can do this on a broad level, by limiting your novel’s voice, narration, scope, or setting: Decide that each chapter can only take place within one location, or devise a set of grammatical rules for your narrator, as I did for Tracy. Follow writer Matt Bell’s lead, who made a rule to keep his protagonist active. “I could write any scene I wanted, in whatever order, as long as my protagonist was doing something that caused a change to occur,” Bell describes in his excellent book on revision, Refuse to be Done. “I discovered the entire plot of the novel by doing this.”

You can also use limitations at the sentence-level. For instance, challenge yourself to write one whole paragraph without using any “tall” letters (b,d,f,g,h,j,k,l,p,q,t,y), as poet Matthew Tomkinson does in his book oems. Assign yourself the task of borrowing a poetic form to write prose (a scene written as a villanelle, for example). Or use one of the exercises from Brian Kiteley’s The 3 a.m. Epiphany, a collection of writing prompts that can be combined or used individually to spark life into an ongoing project. Here’s an example: Tell a story from a person’s childhood, using three sentences from deep inside the child’s POV, and then five sentences from the adult’s POV looking back at this childhood experience. Keep going back and forth this way. 700 words.

That word count is another limitation you can play with, by setting word count limits for each chapter or section. I often use word counts as a revision tactic, rewriting and cutting a draft until it hits a particular number of words. Time offers a similar limitation: You might determine to write nonstop for ten minutes, or twenty, or for the length of a piece of classical music. See what comes of working within the confines of space or time.

It’s no accident that I used the word play. Limitations aren’t just restrictions; they’re also tools—or toys. Go back to the idea of the box: When you give a kid a cardboard box, they don’t see an Amazon shipping container. They see a dollhouse, a racecar, a bed for their imaginary friend, a rocket ship—possibility. When you’ve got limited resources, you get creative.

Next time your writing project grinds to a halt, try taking something away, or setting a few rules. Odds are, playing inside those limitations won’t make you feel restricted; they’ll push you to be even more inventive.

Jamey Bradbury lives and writes in Anchorage, Alaska. She teaches at Alaska Pacific University's new MFA program and at Hiland Mountain Correctional Center. She has an MFA from the University of North Carolina Greensboro. The Wild Inside was her debut novel.

Do you have some limitations you’ve found helpful for sparking creativity or making the blank page less overwhelming? Please do share them! We’d love to hear.

This piece was incredible -- thank you Jamey!!

This is such great advice! You can't think outside of the box if you don't first know what the box is.